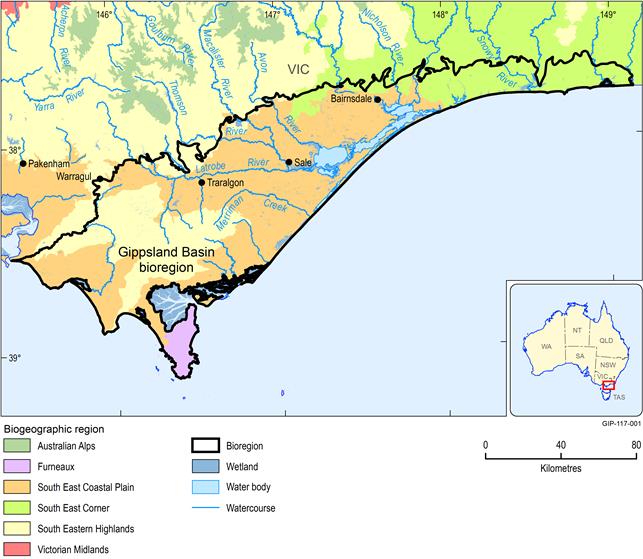

The Gippsland Basin bioregion encompasses a variety of landscapes that provide very high diversity in flora, fauna and habitats. Of the geographically distinct Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation of Australia (IBRA) classification, the South East Coastal Plain IBRA bioregion occupies the largest land area within the Gippsland Basin bioregion (Figure 43). The South Eastern Highlands IBRA bioregion extends to the north-east, with the South East Corner IBRA bioregion to the south, incorporating the Strzelecki Ranges. The Furneaux IBRA bioregion, which encompasses Wilsons Promontory, is the only IBRA bioregion to occur only in the Gippsland Basin bioregion (Figure 43), indicative of the high ecological importance of the area.

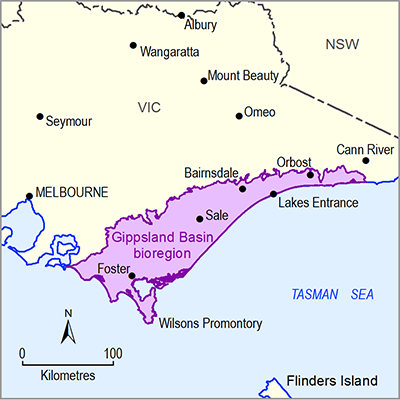

The Gippsland Basin bioregion sits within the boundaries of the West and East Gippsland Catchment Management Authorities. However, it excludes much of the mountainous Great Dividing Range area to the north-west. Rather, the Gippsland Basin bioregion boundary encloses the undulating Gippsland Plains, with coastal features to the south and east. Many significant rivers (Latrobe, Thomson, Mitchell, Avon, Macalister, Tambo and Snowy rivers) flow from the Great Dividing Range across the plains to the south and south-east, draining into the Gippsland Lakes and surrounding Bass Strait.

Vegetation along the north-western edge of the Gippsland Basin bioregion primarily consists of native eucalyptus forest or woodland communities, characteristic of those found in the Great Dividing Range, and dominated by moist and dry foothill forest, some lowland forest, heathy woodland and valley grassy forest. The native grassland and eucalyptus which once covered the South East Coastal Plain IBRA bioregion have been heavily cleared with European settlement to develop agricultural areas on rich alluvial soils. Remaining native vegetation include lowland and foothill forests, temperate rainforest, heath and grassy woodlands as well as coastal scrub and grasslands.

The South East Corner IBRA bioregion (Figure 43) remains heavily forested with native vegetation, including extensive heathland, woodlands and forests on the plain, with dry and damp forest in the foothills, extending into tall wet forest in the highlands and tablelands. This region is nationally significant as a biodiversity reserve for temperate zone biodiversity in Australia, as the only area nationally where native vegetation is continuous from alpine environments to the coast (Department of Natural Resources and Environment 1997).

The Strzelecki Ranges (South Eastern Highlands IBRA bioregion) (Figure 43) are occupied by wet forest in elevated areas, with cool temperate rainforest in protected gullies. Drier foothills consist of lowland eucalypt forest, however, substantial clearing has occurred for agricultural purposes. The nationally listed Giant Gippsland Earthworm (Megascolides australis) is found in the western Strzelecki Ranges and adjoining alluvial soils to the south and south-west.

Wilsons Promontory National Park (Furneaux IBRA bioregion) (Figure 43) maintains the majority of its diverse native vegetation and, as such, was recognised as a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 1981. It is formed of rugged hills, lowlands, beaches and granite headlands and occupied by coastal scrub; heathland; heathy woodland and dry and moist forest. Significant vegetation communities include warm and cool temperate rainforest, and mangroves.

The floristic diversity across the Gippsland Basin bioregion is evident with 28 major vegetation subgroups identified from the National Vegetation Information System (NVIS) Major Vegetation Subgroups (Version 4.1) (Table 20; Figure 44). The diverse landscape provides habitat for unique fauna including birds, frogs, mammals, reptiles and invertebrates. An overlap of southern cool temperate climate zone, along with eastern warm temperate zone in East Gippsland, results in large numbers of flora and fauna native only to East Gippsland. The Gippsland Basin bioregion also maintains high aquatic diversity with rivers, wetlands, estuaries and marine environments (Figure 43). Coastal aquatic areas provide important feeding grounds for migratory birds and habitat for many and varied bird species. Approximately 8350 wetlands are classified within the bioregion (DEPI, 2014), including two Ramsar-listed wetlands. It is broadly thought within the Bioregional Assessment Programme that flora associated with water bodies and/or in the vicinity of water depth of less than 10 m to groundwater will show some level of water dependence.

Land use includes 15 of 18 classes of the Australian Land Use and Management (ALUM) classification scheme (Table 21). Agricultural industry dominates land use with 36% of the Gippsland Basin bioregion under agricultural production. Of this area, less than 2% is irrigated agriculture, which is largely concentrated in the Macalister Irrigation District (adjacent to the Macalister, Thomson and Avon rivers from Lake Glenmaggie to near Sale) (Department of Sustainability and Environment, 2009). The principal agricultural activity is dryland dairy production and beef or sheep grazing on grazing of modified pastures (33%) (Table 21). Plantation forestry is a further major land use (24%) followed by nature conservation (14%). Urban and residential land use totals 11% of the area with less than 3% of the Gippsland Basin bioregion classified as water. Less than 1% of land use is defined as mining and related to brown coal resource, rock and gravel, which is mostly concentrated around Latrobe Valley (GHD, 2014). Recreation and tourism along the coast are important to regional economy.

1.1.7.1.1 Water dependency

Many species and communities, both flora and fauna, are dependent on alternate sources of water (other than rainfall) to survive. These sources might include surface water from streams and wetlands or groundwater either directly from subsurface aquifers, river baseflow or through springs. Groundwater-dependent ecosystems are defined as ‘natural ecosystems that require access to groundwater to meet all or some of their water requirements on a permanent or intermittent basis so as to maintain their communities of plants and animals, ecosystem processes and ecosystem services’ (Richardson et al. 2011). Collectively, these species and communities reliant on alternate water sources are referred to as ‘water-dependent assets’ in the context of the bioregional assessments.

There are a number of water-dependent species and communities in the Gippsland Basin bioregion (Table 22), however knowledge gaps exist for actual water requirements and what the impacts of hydrological change (both surface water and groundwater) might have on their condition.

Data: Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (Dataset 1)

Table 20 National Vegetation Information System (NVIS Version 4.1) major vegetation subgroups in the Gippsland Basin bioregion

Typology and punctuation are given as they are used in the legislation

Data: Department of the Environment and Water Resources (Dataset 2)

Table 21 Australian Land Use and Management land use classes in the Gippsland Basin bioregion

Typology and punctuation are given as they are used in the legislation

Data: ABARES (Dataset 3)