- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

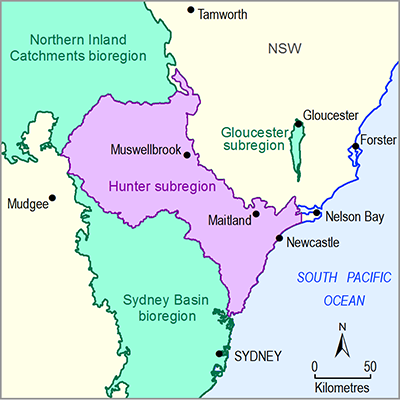

- Hunter subregion

- 1.5 Current water accounts and water quality for the Hunter subregion

- 1.5.1 Current water accounts

- 1.5.1.1 Surface water

- 1.5.1.1.1 Water storage in the Hunter river basin

There are five major storages used for water supply within the Hunter river basin, although only one of these (Grahamstown Dam) is physically within the subregion. They have a combined accessible storage capacity of 1254 GL: Glenbawn (749 GL), Glennies Creek (282 GL), Grahamstown Dam (182 GL), Lostock (19.7 GL) and Chichester (21.5 GL) (Bureau of Meteorology, 2015). Water held in the Glenbawn reservoir is used for flood mitigation, hydro-electric power, irrigation, water supply and conservation. Glenbawn Dam was commissioned in 1947 to secure water for irrigation, industry and town water supply, and for flood mitigation. Construction of a 300 GL reservoir was completed in 1958. In 1987, the dam wall was raised by 22 metres, increasing its storage capacity to 749 GL (plus a potential capacity of 120 GL for flood mitigation). Glennies Creek Dam was built in the 1980s to supplement supplies from Glenbawn Dam. Grahamstown Dam is an off-river storage of which about 50% of inflow is pumped from the Williams River. Its primary purpose is to maintain a sufficient volume buffer to maintain water supply in drought. It is Newcastle’s largest drinking water supply reservoir. On average it supplies about 40% of Newcastle’s drinking water requirements, and a much higher percentage during drought (Hunter Water, 2015b). Chichester Dam on the Williams River is the second largest of Newcastle’s water supply storages, and also services the urban areas around Maitland and Cessnock. Lostock Dam on the Paterson River was built for water conservation and supports irrigation, stock and domestic, town water and environmental water uses.

Lake Liddell (150 GL) and Lake Plashett (67 GL) are two other important storages within the subregion that supply water to electricity generators. Lake Liddell is located near Muswellbrook and supplies cooling water for the Liddell Power Station. Lake Plashett is used as a storage reservoir for Bayswater Power Station. There are other small storages that are used for such things as mine water management and agricultural uses, but their volumes are not reported here.

Table 3 summarises storage volumes at 30 June for the subregion’s five main storages between 1991 and 2012. The day 30 June is the last day of the water year and used in water accounting to quantify closing storage volumes. On average Glenbawn, Glennies Creek and Grahamstown storages close the water year with 70 to 75% of accessible capacity, while Chichester and Lostock storages are typically at 100% of accessible capacity. Glenbawn and Glennies Creek storages recorded their lowest 30 June storage volumes in 2006–07 during the Millennium Drought with 239 GL and 96 GL, respectively, representing approximately 33% of accessible capacity. At Grahamstown, in the same year the 30 June volume was 92% of capacity, whereas 1993–94 was when 30 June volumes were at their lowest (i.e. 64% of capacity, based on capacity priority to augmentation). All three storages were at capacity at the end of 2011–12 following good rainfall in 2007–08 and 2010–11. At Lostock, there is little variation in the 30 June storage volumes over time.

Figure 4 shows the time series of storage volumes at 30 June at Glenbawn, Glennies Creek and Grahamstown storages. Storage volumes at Glenbawn Dam and Glennies Creek Dam exhibit a similar pattern with falling storage volumes from 1991 to 1997 (inflows less than outflows), a period of recovery to 2000 (inflows greater than outflows), before falling again to their lowest volumes in 2006–07. These storage changes largely reflect interannual variations in rainfall. The decline in storage volumes after 2000 can be attributed to the Millennium Drought when precipitation was well below the long-term mean (van Dijk et al., 2013). In contrast, the Grahamstown Dam storage volumes exhibit less variability and a different pattern. Prior to 2005, it had a mean 30 June storage volume of 113 GL, varying from 83 GL in 1993–94 to 133 GL in 2000–01. Following augmentation works in 2005, its storage capacity increased by 50%, leading to higher stored volumes in 2006 and beyond.

Table 3 Storage volumes at 30 June for the five main water supply dams in the Hunter river basin between 1990–91 and 2011–12

aaccessible storage capacity

bstorage volume greater than storage capacity indicates spilling

NA = data not available

Data: Bureau of Meteorology (Dataset 5)

Dashed lines indicate available storage capacity for the three dams with the same colour schemes.

Data: Bureau of Meteorology (Dataset 5)

Product Finalisation date

- 1.5.1 Current water accounts

- 1.5.1.1 Surface water

- 1.5.1.1.1 Water storage in the Hunter river basin

- 1.5.1.1.2 Water storage in the Macquarie-Tuggerah lakes basin

- 1.5.1.1.3 Gauged inflows and outflows in the Hunter river basin

- 1.5.1.1.4 Gauged inflows in the Macquarie-Tuggerah lakes basin

- 1.5.1.1.5 Surface water entitlements and allocations

- 1.5.1.1.6 Water use in the Hunter Regulated River water source

- 1.5.1.1.7 Gaps

- References

- Datasets

- 1.5.1.2 Groundwater

- 1.5.1.1 Surface water

- 1.5.2 Water quality

- Citation

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors to the Technical Programme

- About this technical product