- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

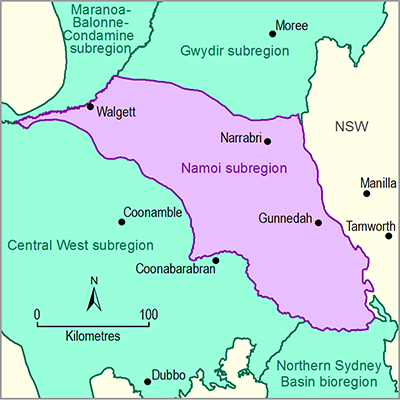

- Namoi subregion

- 1.1 Context statement for the Namoi subregion

- 1.1.5 Surface water hydrology and water quality

- 1.1.5.2 Current water sector allocations

The water balance components of the Lower Namoi River (Figure 44), prepared by the NSW Office of Water, show that in 2012–13 about 33% of total inflow was diverted under access licences while 27% was used for environmental water purposes (end-of-system flow) (Burrell et al., 2014). These values can vary from year to year depending on whether it is an average, dry or wet year (Table 11). Compared to the other two years, 2010–11 and 2011–12 were wet years, with annual rainfall totals for both years well above the long-term average across the entire basin (Burrell et al., 2013). Higher proportions of total flow were diverted under general licences for the drier years of 2009–10 and 2012-2013 than for the wetter years of 2010–11 and 2011–12 (see Table 11).

Figure 44 Lower Namoi River physical flows mass balance diagram for 2012-2013

Source: modified from 2012-13 Namoi Physical Flows Mass Balance Diagram, Burrell et al. (2014, p18)

Table 11 Main components of Lower Namoi River water balance from 2009–10 to 2012–13 showing different flow allocations from year to year

Source data: Burrell et al. (2011a, 2011b, 2013, 2014)

1.1.5.2.1 Water Sharing Plan and restriction on surface water extractions

The ten-year Water Sharing Plan (WSP) (2004–2014) under the New South Wales Water Management Act 2000 establishes long-term average annual extraction limits for Upper Namoi and Lower Namoi Regulated River Water Sources. The aim is to maintain or protect low flows for environmental purposes and to provide equitable access to users (DIPNR, 2004). The Upper Namoi Regulated River Water Source is the water between the banks of all rivers, from the dam wall of Split Rock Dam to the dam wall of Keepit Dam (NSW Office of Water, no date). The Lower Namoi Regulated River Water Source is the water between the banks of all rivers, from the dam wall of Keepit Dam to the junction of Namoi River and Barwon River at Walgett. The Upper Namoi and Lower Namoi Regulated River Water Sources do not include the Peel River.

The Water Sharing Plan for unregulated and alluvial water sources of the Namoi river basin started in October 2012. The plan comprises 22 water sources upstream and downstream of Keepit Dam (NSW Government, 2012).

Levels of extraction in the Namoi subregion are governed by WSP long-term extraction limits and the Murray–Darling Basin Cap. The WSP sets a long-term extraction limit of 238 GL/year from the regulated rivers in the Namoi river basin (excludes Peel catchment regulated river diversions under WSP (MDBA, 2011a). These limits were designed under the environmental water rule, which ensures that flows in the lower reaches of rivers are maintained to reflect natural flow patterns (DIPNR, 2004). All flows above the long-term extraction limit, which amount to approximately 73% of yearly flow in the river on a long-term average basis, are protected for the health of the environment. To protect end-of-system flows, minimum flows are to be maintained in the Namoi River at Walgett during the months of June (≥21 ML/d), July (≥24 ML/d) and August (≥17 ML/d) when water stored in Split Rock and Keepit dams is more than 120 GL (DIPNR, 2004; Barma Water Resources et al., 2012).

Diversion limits and the Basin Plan

The Murray–Darling Basin Authority estimates the surface water long-term average baseline diversion limit for the Namoi river basin (including Peel valley) to be 508 GL/year (MDBA, 2011b). This limit includes 265 GL/year from regulated and major unregulated rivers, and 78 GL/year from minor unregulated rivers (excluding basic rights). The limit on interception by run-off dams is set at 165 GL/year (including 5 GL/year of interception by commercial plantations).

The environmental water requirements of the region have been estimated at between 998 and 1090 GL/year, which is between 31 and 123 GL/year greater than currently available for the environment (MDBA, 2011b). Twenty key environmental assets including Lake Goran, the Namoi and Peel rivers and 17 other rivers and creeks that are potentially dependent on environmental water (see Section 1.1.7 Ecology) have been identified in the region (MDBA, 2010, p 63). Therefore the sustainable diversion limit under the Murray–Darling Basin Plan requires that the surface water long-term average diversion limit be reduced from 508 GL/year by 10 GL/ year to meet local environmental targets plus any apportionment of the northern Basin zone shared reduction target set by the Basin Plan. The SDL will come into effect in 2019 following the completion of the northern basin review, the operation of the SDL adjustment mechanism and apportionment of any shared reduction target in 2016, all of which may lead to further reductions in the Namoi SDL resource unit.

1.1.5.2.2 Rainfall and evapotranspiration

Climate is discussed in Section 1.1.2 Geography. The mean annual rainfall in the Namoi river basin varies from more than 1100 mm/year east of the subregion to about 600 mm/year near Gunnedah to less than 500 mm/year west of Walgett (Figure 10). Rainfall is seasonal with the highest monthly rainfall at Gunnedah being in summer and the lowest during the months of April to September. The average Class A pan evaporation increases from less than 1200 mm/year east of Tamworth, to about 1600 mm/year near Gunnedah, and about 2100 mm/year west of Walgett (Green et al., 2011).

There have been more occurrences of annual rainfalls that are above the long-term mean (622 mm) in Gunnedah since the late 1940s (Figure 45). In comparison, annual rainfall in Narrabri is reasonably uniform with spells of a few years below the long-term mean (653 mm) (Figure 46).

Figure 45 Total annual rainfall at Gunnedah

Orange line shows the long-term annual mean (622 mm)

Figure 46 Total annual rainfall at Narrabri

Orange line shows the long-term annual mean (651 mm)

1.1.5.2.3 Water allocations, licences, extractions and use

Water is allocated to different sectors of water users as per their entitlements. The main sectors are agricultural (including stock water use), domestic, municipal and industrial. The major water users in the Namoi river basin are general security licence holders with a total annual entitlement of 255 GL/year, of which about 10 GL/year is located on the Upper Namoi between Split Rock and Keepit dams (Table 12). The Namoi river basin uses 2.6% of the surface water diverted for irrigation in the Murray–Darling Basin (CSIRO, 2007). Regulated river water and groundwater usage is metered, while usage from unregulated water including floodplain harvesting is currently not metered (Barma Water Resources et al., 2012).

Rapid irrigation development has occurred in the Namoi river basin since the early 1960s, using up to 112,400 ha of land to grow crops (CSIRO, 2007). Major irrigation diversions are made from Keepit, Split Rock and Chaffey dams and Mollee and Gunidgera weirs. The total allocation of water share issued for the regulated Namoi River is nearly 378.9 GL (Table 12) (Green et al., 2011).

High security entitlement of 8 GL exists for town water supply needs for Manilla and Walgett. Stock and domestic replenishment flow rules are also in operation for the Pian Creek system ensuring up to 14 GL in any water year is set aside for delivery downstream of Dundee Weir (see NSW Office of Water (2010) for entitlements relating to other water sources, and further details). When available water in a river cannot be stored, supplementary water access is declared for users to divert water from the river in accordance with their entitlements. A total licensed supplementary cap in the Lower Namoi of 110 GL/year has been implemented.

Table 12 Namoi regulated river share components as at 30 June 2010

Source data: Green et al. (2011)

1.1.5.2.4 Human impacts on the surface water system

Rivers and creeks in the Namoi subregion have been impacted by water regulation and other anthropogenic causes including agriculture and livestock farming. Typically the flow frequency and quantity (e.g. peak discharge and low flows) have been affected (Thoms et al., 1999). Human activities have also affected the physical condition and water quality of the waterways. For example, the Mooki River, Coxs Creek, lower parts of the Namoi River, and the Cockburn River are in ‘very poor physical condition’ as a result of poor land use and farming practices including extraction of sand and gravel. Varying degrees of higher nutrient concentrations along the Namoi River are caused by effluent disposal from sewage treatment plants and unsewered villages (Thoms et al., 1999, page 22).

Increased instances of sediments in creek water due to unrestricted access of livestock have been found. Increased sediment gives rise to increased turbidity and load of other pollutants (e.g. heavy metal, pesticide and nutrients) that are attached to the sediments (Thoms et al., 1999). As described in Section 1.1.5.1.6, residues of pesticides, herbicides and other agricultural chemicals resulting from farming activities, have been detected in rivers and creeks in the Namoi river basin.

1.1.5.2.5 Impacts of climate change on water availability

Yearly flows in the Namoi River at different locations have declined due to frequent below average rainfall since 2000 (see Section 1.1.5.1.4). This is also reflected in the lower volume of water storages in the three major dams (Figure 42) suggesting that water availability in Namoi river basin has been directly affected by climate change and variability.

Impact of future climate

CSIRO (2007) found that future mean annual runoff in the basin is likely to decrease by 6%. The effects of future extreme climate due to a high global warming scenario range from a 31 to 39% reduction in mean annual runoff. The impacts of a low global warming scenario range from a 10% reduction to a 10% increase in mean annual runoff. These effects were assessed for current development pathways in the basin. Effects of climate change with future developments on runoff, end-of-system flow and other aspects of water availability are also described in CSIRO (2007). A study undertaken by the NSW Office of Water also provides estimates of future climate on water availability across NSW (including the Namoi river basin) (Vaze et al., 2008; Vaze and Teng, 2011) suggesting a change in mean annual runoff of ±20% depending on the 15 global circulation models used.

1.1.5.2.6 Impacts of land cover change on water availability

Land use change has a considerable impact on water availability. Although the effects of land use (and other related changes, e.g. water use change) can be seen in the flow reduction in Namoi River at Narrabri (Figure 38 and Figure 39), no study seems to quantify the impacts of these changes on water availability.

Along with land cover change due to agricultural activities, the detention and/or interception of surface runoff in pits of open-cut mines also affects water availability, which affects downstream surface water availability (Schlumberger Water Services, 2012).