The climate varies from temperate conditions with no dry season and warm to hot summers in the east to a more subtropical climate through the centre with areas of no and/or moderately dry winters, to hot, persistently dry climates in the west. Between 1981 and 2012, maximum temperatures averaged 33 to 34 °C through the summer and 18 to 20 °C through the winter, while typical minimum temperatures in summer were 18 to 20 °C and 5 to 6 °C through winter (Figure 11).

|

(a) |

(b) |

|

|

|

Source data: derived from (i) Mean monthly and mean annual rainfall data (Bureau of Meteorology, 2013a) and (ii) Mean monthly and mean annual maximum, minimum and mean temperature data (Bureau of Meteorology, 2013b)

In the subregion, average annual rainfall ranges from more than 800 mm around Toowoomba and Killarney on the Great Dividing Range to about 420 mm near Brewarrina (Figure 12). Figure 13 shows the annual time series of rainfall from 1900 to 2011 for the subregion. The mean annual rainfall for this period is 580 mm, but there is considerable variability with a low of 225 mm in 1902 and a maximum of 1060 mm in 1950. The orange line shows the low frequency trend for the record. The years between 1900 and 1946 were on average drier (530 mm/year) than the latter half of the 20th century (625 mm/year). The millennium drought is not particularly evident in the subregion with the rainfall average of 565 mm for 2002 to 2009 being only slightly lower than that for the full record. Rainfall is summer-dominant, varying from 230 mm (77 mm/month) for the December to February period to 115 mm (38 mm/month) between June and August (Figure 11).

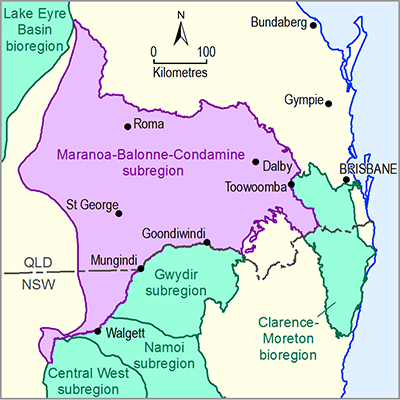

Figure 12 Mean annual rainfall distribution

Potential evapotranspiration (PET) was calculated on a daily time step using the Penman method with a wind spline for the period 1981 to 2012. The spatial pattern of mean annual PET for this period is shown in Figure 13 and varies across the subregion from 1500 mm in the ranges to the east of Warwick to 2370 mm at its most western point. The mean annual PET for the subregion is 2145 mm (1981 to 2012) and varies within the year between 75 mm/month in June to 270 mm/month in December and January, reflecting the annual temperature pattern. On average, evaporation is limited by water availability throughout the year (Figure 11) so actual evapotranspiration rates are not as high as the potential.

Figure 13 Annual rainfall with smoothed rolling average for the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion

Source data: Bureau of Meteorology (2012)

In a recent report by the South Eastern Australia Climate Initiative (SEACI) (CSIRO, 2010), the significance of the 1997 to 2009 drought was assessed relative to other recorded droughts since 1900 and as an indicator of what the future climate might look like. In the Condamine, rainfall was 5 to 20% less than the long-term average and around the Moonie and Macintyre rivers, rainfall was 5 to 10% above the average, but the rest of the subregion experienced about average rainfall. In terms of runoff, the Condamine-Balonne was up to 50% drier than average, while parts of the Moonie and Macintyre valleys were significantly wetter. In general, the impact upon streamflow of a small percentage change in rainfall is enhanced with a 5% reduction in average rainfall leading to a 10 to 15% reduction in streamflow and a 5% increase in rainfall leading to a 10 to 15% increase in streamflow in south-eastern Australia (Chiew, 2006). If the millennium drought is a sign of the future climate, then it would suggest that in the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion the Condamine and Balonne river basins could experience less water availability on average, but the Moonie and Macintyre valleys could experience more water availability.

However, the most recent analysis of likely future climate for the region suggests that the probability of runoff reductions is greater than 50%. Post et al. (2012) modelled future runoff at a 5 km grid resolution for south-eastern Australia. The climate series was informed by simulations from 15 global climate models used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report, taking into account changes in daily rainfall distributions and seasonal rainfall (and potential evapotranspiration) amounts, for an increase in global average surface air temperature of 1.0 °C (2030 relative to 1990), and 2.0 °C (2070 relative to 1990). In the northern Murray–Darling Basin, there is significant variation between models: changes in average rainfall range from 4 to –11% (median of –3%), which correspond to a change in runoff of between 12 and –29% (median of –10%). In the Condamine-Balonne river basin, the median projection under 1.0 °C of warming was for a 4% reduction in rainfall (Table 6) and 13% reduction in runoff (Table 7). In the Moonie river basin, the median projection under 1.0 °C of warming was a 5% reduction in rainfall (Table 6) with a 12% reduction in runoff (Table 7). Across all models, the potential evaporation was projected to increase by 3 to 4% (44 to 70 mm). In summary, increasing temperatures and evaporation and more prolonged drought, combined with periodic extreme flow events, are projected to be the main climate change impacts affecting the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion (EPH, 2009).

Figure 14 Mean annual potential evapotranspiration distribution

Source data: Bureau of Meteorology (2014)

Figure 15 shows the distribution of rainfall and runoff changes across the year for the historical record and projected changes at Toowoomba, in the higher rainfall part of the subregion. Decreases in autumn rains will likely result in reduced runoff, although small decreases in spring runoff do not appear to impact spring runoff. The wider range of projections between January and July for runoff indicate greater uncertainty in runoff projections relative to the rainfall projections. There is far greater consistency between model predictions of late winter to spring runoff predictions, which suggest little change from historical trends during these months.

Table 6 Summary of projected impacts of climate change on rainfall for the broad vicinity of the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion

Source: Table 2 in Post et al. (2012)aGlobal Climate Model

Table 7 Summary of projected impacts of climate change on runoff for the broad vicinity of the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion

Source: Post et al. (2012); their Table 3 aGlobal Climate Model

Source: Figure 18 in Post et al. (2010)

The impacts of climate change in the Maranoa-Balonne-Condamine subregion are projected to be increased pressure on water supplies; reduction in grain quality due to increased temperature, evaporation and decreased rainfall; and increased risk and intensity of bushfires (DERM, 2010). In the DERM (2010) report, which assesses likely climate change impacts in Queensland, it is noted that the impacts of declining rainfall and runoff into streams are already being felt by primary producers and that the effects of temperature changes are likely to be felt within the next decade. Cobon et al. (2009) use a climate change risk management matrix for the Queensland grazing industry, from which they conclude that the combined effect of hotter, drier conditions, changed seasonality of rainfall and more bushfires will likely be a reduction in pasture growth, decreased ground cover, decreased plant available water, more wind erosion and generally long-term negative impacts on ecosystem function. These same negative impacts will be felt by the cropping sector. The assessment of climate change impacts on biodiversity is similarly grim, with projections for declining biodiversity, increasing weeds and pests, landscape-level tree mortality due to water stress and reduced extent and diversity of ecosystems.

The CSIRO attempted to quantify the impacts of a changing climate on the water resources of the Condamine-Balonne (including Maranoa) (CSIRO, 2008a) and Moonie river (CSIRO, 2008b) basins in 2030 based on Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment climate change projections and assuming current levels of development. While the mean runoff reduction forecasts for these basins were 9% and 10%, respectively (relative to the historical average (1895– 2006)), slightly less than the 12% reduction projected in the more recent SEACI report, the assessment of impacts remains relevant. Table 8 summarises impacts on the water resource and wetland inundation events under the best (median) and dry and wet forecast scenarios. For a 9 to 10% reduction in runoff and assuming no new development in the basins (e.g. construction of no new water storages or significant land cover change), the CSIRO estimated 8% and 12% reductions in water availability in Condamine-Balonne and Moonie, 12% and 13% reductions in end-of-system flows and 5% and 6% reductions in diversions in the Condamine-Balonne and Moonie river basins, respectively.

In terms of impacts on wetlands, the CSIRO (2008a) study found that using the median estimate for 2030, the average period between flood events to nationally important wetlands on the lower Balonne River floodplain would increase slightly (9%). Both average flood size and annual flood volume would likely reduce leading to adverse effects on the floodplain vegetation and an 11% reduction in the frequency of years with optimal flows for waterbird breeding habitat. Under the driest scenario modelled, the average period between floods on the lower Balonne River floodplain would increase by nearly two years, the average annual flood volume would be more than halved and there would be a 35% reduction in the number of years with optimal breeding and feeding habitat in the Narran Lakes system. Conversely under the wet extreme, the flood frequency and magnitude would increase somewhat leading to improved conditions on the lower Balonne River floodplain and in the Narran Lakes system.

Depending on the climate change projection, rainfall recharge to groundwater could either increase or decrease; however, the change would not exceed 10%, which is a relatively minor impact on groundwater resources in comparison to groundwater extraction.

There are considerable uncertainties in the climate change projections which make definitive conclusions about the direction and magnitude of changes on water resources difficult to make. However, the SEACI modelling suggests even drier ‘best’ estimates than the earlier studies, so the weight of evidence is for a shift to drier conditions.

Table 8 Projected impacts of climate change on water resources and wetland inundation in 2030 relative to the historical average (1895–2006)

Source data: tables 4-6, 4-7 and 7-2 in CSIRO (2008a); tables 4-4, 4-5, 4-6 and 7-2 in CSIRO (2008b)