- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

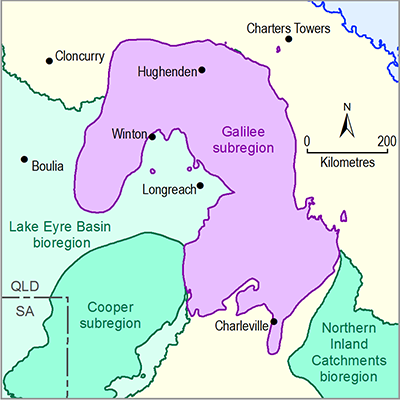

- Galilee subregion

- 1.1 Context statement for the Galilee subregion

- 1.1.7 Ecology

- 1.1.7.2 Terrestrial species and communities

1.1.7.2.1 Principal vegetation types and distribution patterns

Mitchell grass (Astrebla) tussock grasslands is the most widespread terrestrial NVIS v4.1 major vegetation subgroup in the Galilee subregion (32.9% by area, occurring as a largely treeless vegetation type on cracking clay soils and primarily in the northern half of the subregion), followed by Eucalyptus open woodlands with a grassy understorey (16.5%, primarily along the Great Dividing Range in the east of the subregion) and cleared, non-native vegetation, which becomes more abundant towards the south. Twelve other vegetation subgroups each cover 1 to 5% of the subregion (250,000 to 1,250,000 ha each) and 35 vegetation subgroups each cover less than 1% of the subregion (<250,000 ha each). Together with the three most widespread vegetation subgroups, the other less common subgroups form a complex mosaic that grades from north-east to south-west along the main rainfall gradient, but also responds locally to topographic and edaphic variation.

1.1.7.2.2 Recent change and trend

Very early in the Euro-Australian settlement of central and western Queensland, both Mitchell grass tussock (Astrebla) grasslands and Eucalyptus open woodlands with a grassy understorey were recognised as vegetation types with a combination of climatic and edaphic characteristics that would yield high livestock productivity under pastoral grazing systems (Orr and Holmes, 1984; Burrows et al., 1988). After more than a century of extensive cattle grazing, the bulk of these two vegetation types in the Galilee subregion are now classed as ‘modified’, according to the Vegetation Assets, States and Transitions (VAST) classification of Thackway and Lesslie (2001), meaning that the dominant structuring native species are present, but their levels of dominance have been significantly altered, and their natural regenerative capacity is limited or at risk under past and/or current land use or land management practice. According to Thackway and Lesslie (2001), any further modification would involve replacement of the native dominant species by adventive, exotic plant species, and thereby become a class of non-native vegetation.

Concentrated in the eastern parts of the Galilee subregion, 16.1% of the area has been historically and permanently cleared of its native vegetation to make way for non-native pasture, crops, urban development, etc. For the remaining native vegetation, tree clearance remains a source of disturbance and change in the subregion, and occurs primarily to provide or improve the quality of native or semi-natural pasture for cattle. The Queensland Department of Science, Information Technology, Innovation and the Arts (DSITIA, 2012) reported tree clearance during 2010 to 2011 by analysing satellite data in grid cells of 7’30” latitude x 7’30” longitude. Clearance was detected in more than half of the grid cells in the east, centre and south of the subregion, mainly in areas of open woodland characterised by brigalow (Acacia harpophylla), mulga (Acacia aneura) and other acacias and almost exclusively on freehold lands (DSITIA, 2012). The maximum rate of clearance was approximately 5% of a grid cell cleared in the single year, but where clearance occurred the rates were most frequently less than 2% of a grid cell. These rates are all substantially lower than in the past and are part of a trend of declining rates of tree clearance since 2005. In addition, at least two-thirds of the clearance is estimated to be of regrowth, rather than previously uncleared native vegetation (DSITIA, 2012).

As part of Queensland activities for the Australian Collaborative Rangeland Information System (ACRIS), Bastin et al. (2014) have recently completed an analysis of trend in condition of the non-woody component of the native terrestrial vegetation across Queensland’s rangelands, including all non-forested parts of the Galilee subregion. Using multitemporal remote sensing data and analyses based on landscape heterogeneity and functionality, Bastin et al. report that most IBRA subregions within the Galilee subregion showed approximately stable to slightly improving range condition over the period 1988 to either 2003 or 2005 (depending of drought sequences), with the exception being the Alice Tableland IBRA subregion (lying between Hughenden, Pentland, Alpha and Barcaldine, in the north-east of the Galilee subregion) in which range condition declined during the reporting period.

1.1.7.2.3 Species and ecological communities of national significance

Table 10 lists species of national significance listed under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act) that are known to occur in the Galilee subregion through specimens or human observations, or for which their occurrence is likely based upon analysis of the distribution of suitable habitat. Of those species, 23 have been identified as having low or no water dependence in the sense of the BA methodology (Barrett et al., 2013) and thus can be considered terrestrial: 15 plants, two reptiles, two birds and four mammals.

Five terrestrial ecological communities are EPBC listed, as are Coolibah – Black Box Woodlands that are associated with the periodically waterlogged floodplains and margins of various wetlands (Table 10). All occur only in the south-eastern quadrant of the subregion (Figure 55), on relatively fertile soils with relatively high rainfall, and also in areas of largely freehold land, and thus have been subject to selective historical clearance (see Fensham et al. (1998)), grazing, introduction of non-native plant species, and other forms of disturbance. The White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely's Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland in the subregion have the highest EPBC rating (critically endangered).

1.1.7.2.4 Species of regional significance

Table 11 lists taxa of regional significance under Queensland’s Nature Conservation Act 1992. There are 102 taxa that occur in the Galilee subregion but are not also listed nationally.

Source data: Database of Communities of National Environmental Significance. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Canberra, 2013

Table 10 Species and ecological communities in the Galilee subregion that are listed as threatened nationally under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

Source data: Department of Environment, Canberra, 2013

Table 11 Species in the Galilee subregion that are listed as threatened under Queensland‘s Nature Conservation Act 1992 and Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulation 2006 (updated to 27 September 2013), and under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

Source data: Queensland Government (2013)