- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

- Cooper subregion

- 2.3 Conceptual modelling for the Cooper subregion

- 2.3.3 Ecosystems

- 2.3.3.1 Landscape classification

2.3.3.1.1 Methodology

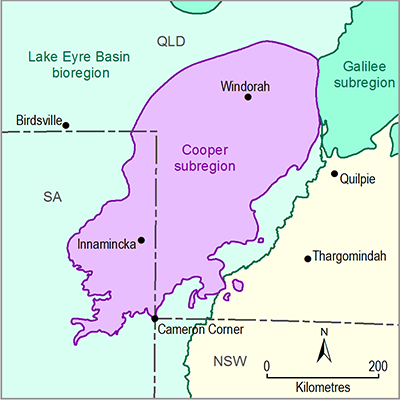

The Cooper subregion is within the Lake Eyre Basin bioregion. It covers an area of 130,000 km2 of which two-thirds is in south-west Queensland with the remainder in north-east SA. The majority of the subregion is within the Cooper Creek – Bulloo river basin with a small part in the north-west within the Diamantina–Georgina river basin. Key features of the Cooper subregion are its large area, sparse human population density (only 1032 residents in the 2011 census) and unpredictable rainfall resulting in natural and human systems driven by resource pulses and boom-bust dynamics. The low human population results in the natural vegetation being relatively intact. The dominant land use in the subregion is grazing of sheep and cattle on natural pastures (grazing native vegetation). Other major land uses are nature conservation and mining (represented by an area of mining and intensive gas treatment, storage and distribution at Moomba). There is no pasture modification or intensive production within the Cooper PAE.

For BA purposes, a landscape classification was developed to characterise the nature of water dependency among the assets of the Cooper PAE. Specifically, landscape classification is used to characterise the diverse range of water-dependent assets into a smaller number of classes for further analysis. It is based on key landscape properties related to patterns in geology, geomorphology, hydrology and ecology. The aim of the landscape classification is to systematically define geographical areas into classes based on similarity in physical and/or biological and hydrological character. The landscape classification includes natural and human ecosystems. The objective of the landscape classification is to present a conceptualisation of the main biophysical and human systems at the surface and describe their hydrological connectivity. Hydrological connectivity describes how biophysical factors such as flow regime influence the spatial and temporal patterns of connection between elements of the water cycle. These elements include surface water and/or groundwater systems (Pringle, 2001). For example, surface water connectivity can be longitudinal along the river channel itself, lateral during overbank flows and vertical where surface water is in contact with underlying groundwater (Boulton et al., 2014).

The landscape classification approach in the BAs provides a mechanism by which receptor impact modelling (product 2.7) can be undertaken on a large number of assets. The rationale for this process is that a landscape class represents a water-dependent ecosystem that has a characteristic hydrological regime. As part of the landscape classification process, the landscape classes are classified into landscape groups. Landscape groups are sets of landscape classes that share hydrological properties. Subsequent in the BA process, the landscape groups are amalgamated into larger entities to enable receptor impact modelling (product 2.7) to take place. However, receptor impact modelling is not being undertaken for the Cooper subregion. Therefore, this landscape classification should be used to assist in clarifying aspects of the conceptual modelling of causal pathways for the Cooper subregion (Section 2.3.5). In particular, it provides clarity on the relative amount of the Cooper PAE that is water dependent and, therefore, likely to be impacted by the coal resource development pathway.

Multiple classification methodologies have been developed to provide consistent and functionally relevant representations of water-dependent ecosystems in Australia and globally. An example is the Australian National Aquatic Ecosystem (ANAE) Classification Framework. The approach outlined in this product has built on and integrated these existing classification systems.

Classification and typology of landscape elements (polygons)

The approach was developed in collaboration with and guidance from experts that have extensive experience with the landscapes of the Cooper PAE both in Queensland and SA. These experts have contributed to the development of similar classification systems such as the ANAE (Aquatic Ecosystems Task Group, 2012a). The classification and typology were developed and refined following a six-step approach that was undertaken for the entire Lake Eyre Basin bioregion and first used for the Galilee subregion. This approach has been applied to the Cooper PAE and is summarised in Table 3.

Table 3 A summary of the six steps undertaken to develop and refine a classification for the Lake Eyre Basin bioregion and then a typology of landscape classes in the Cooper PAE

|

Step number |

Description |

Comment |

|

1 |

Review existing classifications (refer to Section 2.3.3.1.2). |

|

|

2 |

Develop 5-element ANAE-based classification following expert input (3 workshops, Adelaide and Brisbane). |

A typology of 180 potential landscape classes was developed. |

|

3 |

Apply classification to Cooper datasets followed by initial lumping of some elements (e.g. ‘Landform’ was reduced from five categories to two, specifically; wetland (including estuarine, riverine, lacustrine, palustrine) and non-wetland). |

A typology with 27 landscape classes was developed. |

|

4 |

Apply ‘Broad Habitat’ element to each of the landscape classes where applicable. Thus each existing class can be ‘remnant’ or ‘non-remnant’. |

Typology modified to include 50 potential landscape classes. |

|

5 |

Expert feedback sought on the modified typology. |

Typology undergoes minor refinement. |

|

6 |

Further reduce typology by lumping of categories within some elements. Specifically, near-permanent and intermittent lumped for ‘Water Availability’. ‘Water Type’ only considered for disconnected wetlands. |

Final typology established. |

The classification is based on five elements derived from the ANAE. The first division is based on topography and is at level 2 (landscape scale) of the ANAE structure. The Cooper PAE is divided into floodplain and non-floodplain areas. This division allows broad classification of which landscape components might be influenced by flooding regimes that are more likely to support water-dependent biota.

The next division is based on landform and is at ANAE level 3 (system). Polygons were divided into wetland and non-wetland. Wetlands were classified as either lacustrine, palustrine or riverine based on the wetland class field in the Queensland wetland mapping (DSITIA, Dataset 3) and South Australian wetlands groundwater-dependent ecosystem (GDE) classification (DEWNR, Dataset 4).

The remainder of the classification was based on habitat variables also at level 3 of the ANAE structure. These variables were water type, water availability and groundwater source, specifically:

- water type (brackish/saline, fresh)

- water availability (permanent, near-permanent (wet greater than 80% of time), intermittent or ephemeral)

- water source ( groundwater dependent or non-groundwater dependent).

Water availability and water type were inferred from Queensland and SA wetland and GDE mapping datasets (DSITIA, Dataset 2; DSITIA, Dataset 3; DEWNR, Dataset 4). Water type was determined from wetland mapping for wetlands and from GDE mapping for non-wetlands.

In addition to the five elements of the classification derived from the ANAE, an additional variable was used that identified a polygon as either remnant or non-remnant vegetation. This distinction is based on the Queensland remnant regional ecosystem (RE) mapping from 2013 (Queensland Herbarium, Dataset 1). This approach distinguishes relatively intact from ‘human-modified’ landscapes. This distinction has consequences for defining where important habitats and biota may occur when considering assets and their likely distribution.

During development of the landscape classification for the Lake Eyre Basin bioregion a number of differences in structure between the current ‘fit-for-purpose’ classification and that of the Lake Eyre Basin River Monitoring Project (LEBRM) (Miles and Miles, 2014) were identified. A summary of additional elements from the LEBRM Classification Framework that were considered during the classification process is provided in Table 4. It should be noted that although the additional information was often deemed to be useful, in several cases the data were not available. Furthermore, although the LEBRM is also based on the ANAE, several additional elements come from the South Australian Aquatic Ecosystems (SAAE) Classification Framework (Fee and Scholz, 2010)

Table 4 A summary of additional elements that were considered when developing the landscape classification for the Lake Eyre Basin bioregion

A spatially complete layer of all classed polygons was produced by using geographic information system (GIS) software to run a spatial union on the input layers that included the remnant and non-remnant features. Landscape classes were defined using the five elements from the ANAE structure with their nomenclature reflecting key water dependency attributes (Table 5). As an example, an area classified as ‘remnant’, ‘non-floodplain’, ‘wetland’, ‘disconnected, ‘saline’ has the landscape class: ‘Non-floodplain disconnected saline wetland, remnant vegetation’. In other words, this area is not on a floodplain and is surface water dependent (not connected to groundwater) and associated with a saline wetland.

Classification and typology of the stream network

Streams in the PAE were classified based on their catchment position, water regime and association with GDEs. Catchment position (i.e. upland versus lowland) is of limited use in the Cooper PAE compared to other subregions with a stronger elevational gradient. In the Cooper PAE there is a general increase in salinity, aridity and flow duration from upper to lower sections of the catchment. Rivers and streams can also receive significant baseflow inputs from local and regional groundwater systems and act as recharge sources to support GDEs. Water regime is critical in determining suitable habitat for biota and physical features of the channel and riparian zone.

The stream network had not previously been classified in the Cooper PAE, which meant that the Assessment team completed this part of the landscape classification. The stream network data were based on the Geofabric v2 cartographic mapping of river channels derived from 1:250,000 topographic maps (Bureau of Meteorology, Dataset 5). The Geofabric is a purpose-built GIS that maps Australian rivers and streams and identifies how stream features are hydrologically connected. The water regime of these stream networks was also defined (near-permanent or temporary) using the Queensland pre-clearing and remnant ecosystems mapping data (Queensland Herbarium, Dataset 1). Mapping of valley bottom flatness (MrVBF) (CSIRO, Dataset 6) was used to classify streams as either upland or lowland following methods outlined in Brooks et al. (2014).

2.3.3.1.2 Landscape classification

Typology of landscape classes

The Assessment team defined a set of landscape classes that represent the main biophysical and human systems in the Cooper subregion. This typology consists of 19 landscape classes that can be reduced into 8 landscape groups (Table 5 and Table 6). The distribution of landscape classes in the Cooper subregion is shown in Figure 19.

The typology includes aspects of existing wetland models such as those developed for Queensland that form part of the Queensland Government’s WetlandInfo website (DERM, 2015). Similar wetland models are available for wetlands in other areas of the Lake Eyre Basin bioregion. These include models intended to cover the entire Lake Eyre Basin (Imgraben and McNeil, 2015), NSW including arid regions (Claus et al., 2011) and the semi-arid (northern) section of the Murray-Darling Basin (Price and Gawne, 2009). Each of these suites of models was consulted in the development of the landscape classification for the Lake Eyre Basin bioregion (Table 3, step 1). However, each has strengths and weaknesses and none covers the entire geographical area or environmental heterogeneity needed. Therefore, no existing approach was considered suitable to adopt in its entirety for the BA for the Cooper subregion. The concordance of the Lake Eyre Basin typology with that from Queensland Government’s WetlandInfo, as an example, is summarised in Table 7.

The typology of landscape classes included two landscape classes that are non-water dependent: ‘Dryland’ and ‘Dryland, remnant vegetation’. Together, these landscape classes occupy 75.36% of the Cooper PAE (Table 5). Of the water-dependent landscape classes, the area covered by floodplain and non-floodplain landscape classes is 13.10% and 11.54%, respectively.

Naming conventions for landscape classes

The naming conventions for polygon landscape classes are detailed below.

- Floodplain/non-floodplain. Out of the ten landscape classes that are non-floodplain, all but two non-floodplain landscape classes have ‘non-floodplain’ as the first word of the landscape class name. The exceptions are the two landscape classes (which are non-floodplain, non-wetlands) in the ‘Dryland’ landscape group. ‘Floodplain’ is used in the name only for the landscape classes that are ‘disconnected’ (surface water dependent, not connected to groundwater).

- Wetland/non-wetland. The next word in the name of each landscape class indicates if it is a wetland or not. If it is a wetland, it will either be a groundwater-dependent ecosystem (‘wetland GDE’) or surface water-dependent ecosystem (‘disconnected wetland’). If the landscape class is not a wetland, the term ‘non-wetland’ or ‘terrestrial’ will appear.

- Salinity. Saline disconnected wetlands are indicated as ‘disconnected saline wetland’. Salinity is indicated only for disconnected wetlands.

- Remnant/non-remnant. The broad habitat separation of ‘remnant’ or ‘non-remnant’ is indicated last in the landscape class name. Only the term ‘remnant vegetation’ is included in the name of the landscape class. If this does not appear, then the landscape class is ‘non-remnant vegetation’.

The stream network is defined from a smaller set of criteria. The naming conventions for streams follow this order: ‘temporary’ or ‘near-permanent’, then ‘lowland’ or ‘upland’.

Table 5 Typology of landscape classes in the Cooper PAE based on polygons with land area and percentage of PAE

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

Table 6 Typology of stream network classes in the Cooper PAE with total length and percentage of total stream network in the PAE

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

Figure 19 Landscape classes of the Cooper PAE

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

Boxes indicate areas of interest that are covered by Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23 and Figure 24.

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem

Table 7 Comparison of the landscape classes and landscape groups from the Cooper PAE classification and typology with the Queensland WetlandInfo models

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem; GAB = Great Artesian Basin

2.3.3.1.3 Description of landscape classes

This section provides a description of the landscape groups in the classification. Eight landscape groups are recognised.

Floodplains

A floodplain can be defined broadly as that area of a landscape that occurs between a river system and the enclosing valley walls and is exposed to inundation or flooding during periods of high discharge (Rogers, 2011). For the Lake Eyre Basin, floodplains are considered to be alluvial plains that have an average recurrence interval of 50 years or less for channelled or overbank streamflow (Aquatic Ecosystems Task Group, 2012b). Floodplain and lowland riverine areas derived from Quaternary alluvial deposits are widely distributed across the Cooper PAE. The river systems within the Cooper subregion feature extensive floodplains. For example, in some areas the breadth of the floodplain of the Cooper Creek exceeds 60 km.

‘Floodplain, non-wetland’ landscape group

Some areas of floodplain within the Cooper PAE are classed as disconnected, non-wetland. The ‘Floodplain, non-wetland’ landscape group supports terrestrial vegetation that is not groundwater dependent and relies on rainfall and local runoff. Within the PAE the landscape class ‘Floodplain, disconnected non-wetland, remnant vegetation’ is prominent in the north-east, bordering the eastern margin of Cooper Creek floodplain, and in the east bordering the Wilson River (Figure 19).

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

The location of this map is identified by box #1 in Figure 19.

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

The location of this map is identified by box #2 in Figure 19.

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem

‘Floodplain or lowland riverine wetland GDE’ landscape group

Wetland GDEs occupy 8.82% of the PAE (Table 5). This landscape group includes palustrine and lacustrine wetlands that are groundwater dependent. Extensive areas of the Cooper Creek floodplain in south-west Queensland and west of Innamincka, SA, are in the ‘Wetland GDE, remnant vegetation’ landscape class (Figure 19).

Discharge spring wetlands are a well-known type of wetland that depend on groundwater and are of high importance in terms of biodiversity values. Two discharge springs occur within the Cooper PAE, at Lake Blanche in the extreme south-west. The springs form part of the Lake Frome spring supergroup. This spring supergroup is part of a threatened ecological community that is listed in the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), ‘The community of native species dependent on natural discharge of groundwater from the Great Artesian Basin’. The community occurs in parts of NSW, Queensland and SA (Fensham et al., 2010). It is listed as endangered.

Figure 22 Landscape classes in the vicinity of Cooper Creek, north-east South Australia

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

The location of this map is identified by box #3 in Figure 19.

‘Floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group

The ‘Floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group contains landscape classes that have a subsurface reliance on groundwater sources. Floodplain, terrestrial GDEs occupy 3.58% of the Cooper PAE (Figure 19 and Table 5). The landscape matrix between the Grey Range and Warri Warri Creek in south-west Queensland has several areas of landscape in the ‘Terrestrial GDE, remnant vegetation’ landscape class (Figure 21).

Terrestrial GDEs typically consist of terrestrial vegetation of various types (open-forest, woodland, shrubland, grassland) that require access to groundwater on a permanent or intermittent basis to meet all or some of their water requirements. These landscapes are dependent on the subsurface presence of groundwater, which is accessed via their roots at depth. Examples of terrestrial GDEs in the PAE include riparian vegetation such as river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) open forest and coolibah (Eucalyptus coolabah) woodland.

‘Floodplain or lowland riverine disconnected wetland’ landscape group

The ‘Floodplain or lowland riverine disconnected wetland’ landscape group includes all floodplain landscape classes that depend predominantly on surface water such as flood flows from rainfall events, direct precipitation and local runoff. These wetlands are usually separated from the underlying groundwater system by an unsaturated zone; if groundwater seepage does occur it is not the main source of water.

Three landscape classes in this group occur in the Cooper PAE: ‘Floodplain disconnected wetland, remnant vegetation’, ‘Near-permanent, lowland stream’ and ‘Temporary, lowland stream’. The landscape group makes up less than 1% of the PAE based on the area of polygons. In contrast, the ‘Temporary, lowland stream’ landscape class makes up 94.59% of the stream network and is visible in all the landscapes mapped in this product (Figure 19 to Figure 24).

Remnant vegetation associated with disconnected wetlands includes woodland of river red gum, coolibah or river cooba (Acacia stenophylla), and shrubland of lignum (Muehlenbeckia florulenta) and northern bluebush (Chenopodium auricomum).

Waterholes within river channels are included in this landscape group. Waterholes are of considerable importance in that they continue to hold water once flow in river channels ceases. Thus waterholes act as refuges for aquatic biota when natural fragmentation occurs during dry periods and play a key role in sustaining assemblage dynamics and ensuring persistence of populations (Arthington et al., 2010; Arthington and Balcombe, 2011; Kerezy et al., 2011). Populations in waterholes disperse widely once flooding occurs leading to cycles of expansion and contraction of aquatic biota such as fish (e.g. Kerezy et al., 2013).

Waterholes may or may not interact with groundwater depending on the level of substrate permeability and depth to groundwater. The majority of waterholes in Cooper Creek are not groundwater dependent (Fensham et al., 2011). Although surface water-dependent waterholes lose water through evaporation, suspended clays that settle out after flow events form a bottom seal that minimises seepage loss.

Non-floodplains

Drylands, as well as areas that are not on the floodplain and are not wetlands, are the major landscape groups in the Cooper PAE. A further three landscape groups are water dependent but do not occur on floodplains (Table 5): ‘Non-floodplain (including upland riverine) wetland GDE’, ‘Non-floodplain (including upland riverine) disconnected wetland’ and ‘Non-floodplain, terrestrial GDE’. Most landscape classes within these landscape groups consist of GDEs.

‘Dryland’ landscape group

Drylands receive water from rainfall and local runoff. The majority of the Cooper PAE is arid or semi-arid, with a mean annual rainfall of less than 300 mm (see Figure 10 in Smith et al., 2015). Only a limited area along the eastern margin of the PAE receives greater than 300 mm of rainfall on average annually. Rainfall within the PAE and throughout arid and semi-arid northern and central Australia is highly unpredictable (van Etten, 2009) and occurs in discrete pulses. As a consequence, land systems such as drylands experience irruptive pulses in primary productivity and support a biota that undergoes boom-bust population dynamics. Boom-bust population dynamics are also a strong feature of wetland systems in the Cooper PAE (Arthington et al., 2010; Arthington and Balcombe, 2011).

Most of the Cooper PAE is dryland that supports remnant vegetation. Specifically, the ‘Dryland, remnant vegetation’ landscape class comprises 74.74% of the PAE (Figure 19). The predominance of this landscape class is apparent in the landscape classes in the extreme north-east of the PAE (Figure 20), where most of the area is in the ‘Dryland, remnant vegetation’ landscape class.

A wide range of vegetation types occur within the ‘Dryland’ landscape class. The major vegetation assemblage is chenopod shrubland – specifically saltbush and/or bluebush shrubland, which occupies 22.3% of the subregion by area. Other major vegetation types include Mitchell grass (Astrebla) tussock grassland, spinifex (Triodia) hummock grassland, and Mulga (Acacia aneura) open woodland and sparse shrubland.

‘Non-floodplain (including upland riverine) wetland GDE’ landscape group

Non-floodplain wetland GDEs occupy 5.0% of the Cooper PAE but are patchily distributed (Figure 19). An area that is dominated by this landscape group is Lake Blanche, a salt lake located on the south-west boundary of the Cooper PAE (Figure 19). The main landscape class is ‘Non-floodplain wetland GDE’ with small areas of ‘Non-floodplain wetland GDE, remnant vegetation’. The northern shore of Lake Blanche is fringed by ‘Dryland’ then ‘Dryland, remnant vegetation’ landscape classes (Figure 23).

In the central parts of the Cooper PAE, sand dunefields (sand ridges) are an important source of groundwater, which supports non-floodplain wetland GDEs. These dunefields can store groundwater in local, intermediate or regional groundwater flow systems and also in perched aquifers formed by layers of relatively impermeable clay-dominated material. Palustrine, lacustrine and riverine wetlands on the edge of inland sand dunefields may be present because of the surface expression of this groundwater.

‘Non-floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group

The details of the ‘Non-floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group are similar to the ‘Floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group although the former landscape group occupies more of the PAE (6.28%). The ‘Non-floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group is particularly concentrated in the central and the extreme east of the PAE (Figure 19).

Terrestrial GDEs are typically terrestrial vegetation of various types (open-forest, woodland, shrubland, grassland) that require access to groundwater on a permanent or intermittent basis to meet all or some of their water requirements. In the case of non-floodplain environments, terrestrial GDEs tend to be on loamy or sandy plains or inland sand dunefields (sand ridges), which are composed largely of unconsolidated sand deposited by aeolian processes (wind). Landscape classes in the ‘Non-floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group are dependent on the subsurface presence of groundwater, which is accessed via their roots at depth. For inland sand dunefields, groundwater is available from unconsolidated sedimentary aquifers from which terrestrial vegetation typically accesses water through the capillary zone above the watertable.

A landscape that has significant areas that are in the ‘Non-floodplain, terrestrial GDE’ landscape group is shown in Figure 21. Here, streams that are in both ‘Temporary, lowland streams’ and ‘Temporary, upland streams’ landscape classes flow from the Grey Range towards Warri Warri Creek. Extensive areas of ‘Non-floodplain terrestrial GDE, remnant vegetation’ occur in the west of the area (Figure 21). Similarly, the landscape in the vicinity of Cooper Creek and Coongie Lakes, SA, has patches of ‘Non-floodplain terrestrial GDE’ and ‘Non-floodplain terrestrial GDE, remnant vegetation’ along drainage lines (Figure 24).

‘Non-floodplain (including upland riverine), disconnected wetland’ landscape group

Landscape groups that contain ‘non-floodplain disconnected wetland’ include all non-floodplain landscape classes that depend on surface water such as flood flows from rainfall events. Landforms included are lacustrine, palustrine and riverine. Also included are riverine elements such as waterholes. The landscape groups include saline/brackish and freshwater wetlands with water availability being usually non-permanent or near-permanent. Non-floodplain disconnected wetlands make up a small area (0.26%) of the PAE based on polygons (Table 5) and 5.43% of the total stream network. A landscape that includes small patches of ‘non-floodplain disconnected wetland, remnant vegetation’ and ‘non-floodplain disconnected saline wetland, remnant vegetation’ is shown in Figure 22. Here the disconnected wetlands occur at the boundary of floodplain wetland GDEs and dryland, south-west of Innamincka.

Rockholes are a type of wetland only present in landscape groups that contain non-floodplain, disconnected wetlands. Rockholes are natural hollows in rocky landscapes that form by fracturing and weathering of rock and which store water from local runoff (Fensham et al., 2011). Typically, rockholes occur in sandstone and granite ranges. As with other wetlands in these landscape groups, most rockholes are non-permanent.

Figure 23 Landscape classes along the north portion of Lake Blanche, north-east South Australia

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

The location of this map is identified by box #4 in Figure 19.

Data: CSIRO (Dataset 7)

The location of this map is identified by box #5 in Figure 19.

Modified landscapes

As mentioned previously, very little of the Cooper PAE includes human-modified landscapes. The PAE does not include any dryland cropping or horticulture, irrigated cropping or horticulture, grazing of modified pastures or intensive horticulture or animal production. The main impact on water-dependent ecosystems from human activity is the placement of bores to provide water at the surface for livestock. Bores rely on groundwater and in the past have had a significant negative impact on springs adjacent to the PAE (Fensham and Fairfax, 2003; Fensham et al., 2011). Urban settlement is very limited in extent and the towns that do exist have small populations.