- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

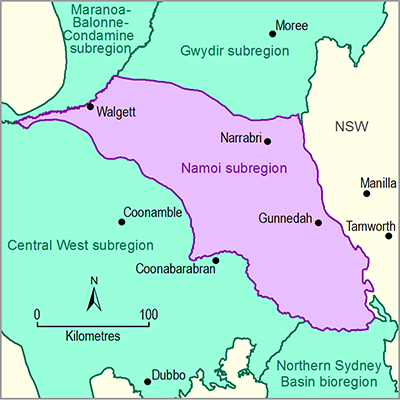

- Namoi subregion

- 2.7 Receptor impact modelling for the Namoi subregion

- 2.7.7 'Springs' landscape group

- 2.7.7.2 Qualitative mathematical model

Workshop discussions on the ‘Springs’ landscape group in the Namoi subregion identified a general lack of knowledge about the actual locations of springs in the basin, however, it was concluded that, with respect to the potential impacts of coal resource development, the focus of modelling should address those springs thought to be in the zone of potential hydrological change. These springs were identified as most likely to be recharge springs (Fensham and Fairfax, 2003) (Figure 34). The experts in the workshop defined the flow path of these springs as originating from water that is absorbed into sandstone that outcrops on the margins of the GAB and later discharges locally after relatively short residence times.

The saturated zone or water depth of the spring was taken as a critical threshold; water depths above this threshold increased the amount of vegetation surrounding the spring (i.e. fringe vegetation), the amount of open water in the spring, and the amount of outflow (Figure 36). Below this threshold many of the ecological values of the spring cease to exist (Figure 36). Fringe vegetation provides habitat and other resources for populations of semi-aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, which in turn are a food resource for frogs and terrestrial invertebrates, also living in the fringing vegetation (Fensham et al., 2004). While terrestrial invertebrates are considered an important food resource for their predators, the predator population in return was not considered to have a significant effect on their prey, thus there is no negative link back to terrestrial invertebrates from their predators in the models. Populations of submerged macrophytes depend on the amount of open-water habitat and contribute to stores of organic matter (Figure 36). This organic matter is a primary resource for tadpoles and aquatic invertebrates, which also depend on the volume of open-water habitat.

The amount of open-water habitat in a spring, and its depth, can be controlled by the structural influence of dams, excavations, and mud mounds (Fensham et al., 2012). The intensity of cattle grazing and populations of pigs, however, can dramatically diminish the depth of the open-water habitat by trampling and eroding its edges (Figure 36).

For recharge springs, the relative depth of a spring is determined by the level of the watertable (Figure 36). When the depth of the watertable falls below the bottom of the spring, subsurface habitats are vulnerable to drying, which can diminish the groundwater biota and invertebrate egg bank (Lamontagne, 2002). This invertebrate egg bank, which exists in the bottom and near-surface sediments of the spring, is an important source of propagules that allow the spring’s invertebrate community to recover after drying spells (Ponder, 1986) (Figure 36).

The amount of precipitation and infiltration was inferred to contribute to groundwater. Coal resource development, through coal seam gas extraction and open-cut mines, could potentially lower the watertable, and thus impact the depth of recharge–rejection springs (Figure 36).

Figure 36 Signed digraph model of recharge-rejection spring ecosystem

Model variables are: algae (Alg), coal resource development (CRD), dams, excavations and mud mounds (DEMM), fringing vegetation (FV), frogs (Frogs), grazing and pigs (G&P), groundwater biota and invertebrate egg bank (GB&IEB), groundwater table levels below spring (GWT<S), groundwater table levels above spring (GWT>S), invertebrates (aquatic) (Inv), organic matter (OM), open water (OW), precipitation and infiltration (Ppt), predators (Pre), semi-aquatic invertebrates (SAI), spring depth above wetted level (SD>W), submerged macrophytes (SMP), spring outflow (SO), subsurface habitat (SSH), terrestrial invertebrates (TI), tadpoles (TP).

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 2)

Surface water and groundwater modelling predict significant potential impacts to the level of the watertable. This impact was split into changes in depth of groundwater that was above (GWT>S) and below (GWT<S) the base of the springs, which was developed into two cumulative impact scenarios (Table 47).

Table 47 Summary of the (cumulative) impact scenarios (CIS) for the recharge–rejection spring ecosystem

|

CIS |

GWT>S |

GWT<S |

|---|---|---|

|

C1 |

– |

0 |

|

C2 |

– |

– |

Pressure scenarios are determined by combinations of no-change (0) or a decrease (–) in the following signed digraph variables: decrease in groundwater table level when spring is wet (GWT>S) and decrease in groundwater table below spring level (GWT<S).

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 2)

Qualitative analyses of the signed digraph model (Figure 36) generally indicate an ambiguous or negative response prediction for all biological variables within the recharge–rejection spring as a result of a drop in the level of the watertable (Table 48).

Table 48 Predicted response of the signed digraph variables in the recharge–rejection spring ecosystem to (cumulative) changes in hydrological response variables

Qualitative model predictions that are completely determined are shown without parentheses. Predictions that are ambiguous but with a high probability (0.80 or greater) of sign determinancy are shown with parentheses. Predictions with a low probability (less than 0.80) of sign determinancy are denoted by a question mark. Zero denotes completely determined predictions of no change.

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 2)

Product Finalisation date

- 2.7.1 Methods

- 2.7.2 Prioritising landscape classes for receptor impact modelling

- 2.7.3 'Floodplain or lowland riverine' landscape group

- 2.7.4 'Non-floodplain or upland riverine' landscape group

- 2.7.5 Pilliga riverine landscape classes

- 2.7.6 'Rainforest' landscape group

- 2.7.7 'Springs' landscape group

- 2.7.8 Limitations and gaps

- Citation

- Acknowledgements

- Contributors to the Technical Programme

- About this technical product