- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

- Sydney Basin bioregion

- 1.3 Water-dependent asset register for the Sydney Basin bioregion

- 1.3.1 Methods

- 1.3.1.3 Determining the preliminary assessment extent

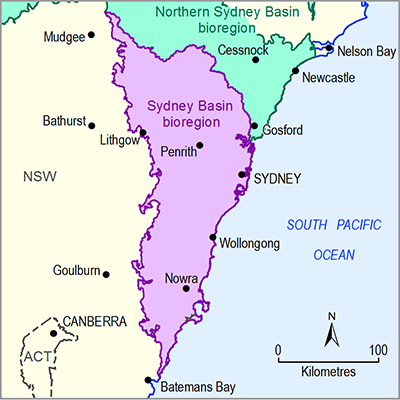

The Sydney Basin bioregion is defined to the north by the surface water catchment divide between the Hawkesbury-Nepean river system and Hunter River, to the east mainly by the coastline, and to the south and west by the geological boundary defining the Sydney geological basin. This western geologically-defined boundary only approximates the surface water divide between east-flowing coastal rivers and those flowing westward as part of the Murray-Darling Basin. Most (94%) of the Sydney Basin bioregion land area drains east to the Tasman Sea or to coastal lakes, with the remaining 6% (or 153,018 ha) being part of the Macquarie-Bogan river basin that is part of the Murray-Darling Basin (see Section 1.3.1.4).

To help guide the development of the PAE, a list of new coal mine proposals and existing coal mines with plans to expand mining areas, extend timelines and/or modify existing development approvals beyond December 2012 was compiled by the Assessment team in mid-March 2015. The list was compiled primarily from the NSW Major Projects website (NSW Planning and Environment, 2016), which tracks the assessment of development proposals of state significance, and mining company websites. Areas with identified coal resources with no development application were not included, although they are identified in companion product 1.2 for the Sydney Basin bioregion (Hodgkinson et al., 2018). The March 2015 PAE mines included 13 coal mines in the bioregion, comprising 10 underground mines (Airly, Angus Place, Appin, Clarence, Dendrobium, Russell Vale, Springvale, Tahmoor, Wongawilli and West Cliff) and three open-cut coal mines (Cullen Valley, Invincible and Pine Dale). Although there is an existing CSG development at Camden, there were no proposals for post-2012 expansions or new CSG developments at this time. At March 2016, when the coal resource assessment for the Sydney Basin was completed (Hodgkinson et al., 2018), only seven of the PAE mines were identified as having post-2012 development plans (i.e. Airly, Angus Place, Hume, Pine Dale, Russell Vale, Springvale and Wongawilli). The impact of including the six other mines in defining the PAE means that the PAE could be larger than it needs to be, with the consequence that potentially more assets have been included in the water-dependent asset register for the Sydney Basin bioregion. Since March 2015, Director-General’s Environmental Assessment Requirements (DGRs) have been issued for Hume Coal mine and an environmental impact statement (EIS) is expected to be completed in 2016. This development proposal was not sufficiently progressed at the time to be included in the list of mines used to define the PAE, and development of this proposal has occurred quite quickly. Centennial Coal is undertaking exploration drilling at Inglenook and Neubeck, both areas with identified coal resources. While they were not used to define the PAE, they are located within the PAE that has been defined using the 13 coal mines. Note Cullen Valley was mistakenly treated as an underground mine (historically it was) in the analysis to define the PAE. This has no impact on the resultant PAE as the mine is close to the Sydney Geological Basin boundary (which limits extent of groundwater impacts), close to other mines used in defining the PAE (i.e. large overlapping potential impact zone), and has been in care and maintenance since December 2012 with no future development plans.

Mine site locations were obtained from either the OZMIN database (Geoscience Australia, Dataset 43) or the MinView database (Trade and Investment, NSW, Dataset 44), and these were then checked against existing tenement boundaries (such as mining leases) to confirm the locations. Figure 3 shows the location of these mines. To define the PAE, that is, the area surrounding the mines that could potentially be affected by current and future coal resource developments, the approach needs to reflect potential impacts upon groundwater, surface water and surface water – groundwater connectivity. Each of these is considered in the following sections.

Figure 3 Location of the Sydney Basin bioregion, coal mines with expansion plans, and major rivers

Data: DTIRIS (Dataset 45); Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44)

1.3.1.3.1 Groundwater considerations

To define the PAE based on groundwater impacts for the Sydney Basin bioregion, the maximum distance from each mine site that could be affected by groundwater drawdown was estimated. In the Western Coalfield, the western boundary of the geological Sydney Basin (which defines the western boundary of the Sydney Basin bioregion) forms a hydrogeological boundary across which it is assumed there is no groundwater connectivity (strictly speaking, this will not necessarily hold true for an alluvial aquifer sitting atop the geological Sydney Basin strata, from which groundwater could flow across a geological divide, but this connectivity is dealt with in defining the surface water PAE). Thus, it is assumed that deeper groundwater units to the west of this divide are not influenced by the longwall coal mines located in the bioregion. In the Southern Coalfield, the coastline to the east forms a natural boundary beyond which any impacts on groundwater from coal mining are swamped by the influence of the Tasman Sea and occur outside the bioregion for the purposes of the BA.

In the longwall operations, the target coal seams can be many hundreds of metres below ground level and separated from the surface assets via a sequence of aquitards and aquifers (see companion product 1.1 for the Sydney Basin bioregion (Herron et al., 2018a) for more detail). The sequence of aquitards and aquifers will attenuate the drawdown signal such that it will be reduced, possibly not even evident, at the surface and delayed in time. Drawdowns from open-cut mines will occur where the operations intersect the water table aquifer. The groundwater numerical modelling for the BAs for the Gloucester subregion (companion product 2.6.2 for the Gloucester subregion (Peeters et al., 2018)) and Hunter subregion (companion product 2.6.2 for the Hunter subregion (Herron et al., 2018b)) show that drawdowns at the surface do not propagate more than 20 km from any of the mines in those regions by 2102. Based on the geological similarity of the Sydney Basin bioregion and Hunter subregion in particular, a maximum radius of 20 km from each mine was adopted to define the groundwater PAE for the Sydney Basin bioregion. The combined effect of these natural and 20 km radial boundaries are shown in Figure 4, leading to two disparate groundwater PAE components: one in the Western Coalfield around the mining developments near Lithgow, and the second in the Southern Coalfield around the mining developments west of Wollongong.

Figure 4 Groundwater preliminary assessment extent (PAE) in the Sydney Basin bioregion

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46)

1.3.1.3.2 Surface water considerations: open-cut mines

To determine the extent to which the hydrological impacts of open-cut coal mines propagate downstream of the mine sites, the runoff contribution from the mine footprint relative to the runoff contribution of the rest of the catchment is compared at different distances from the mine site. This modelling requires three main inputs (i) locations of the open-cut coal mine pits in December 2012 as determined from satellite imagery; (ii) a set of catchments that include, and are downstream from, the open-cut mines – obtained here from the Australian Hydrological Geospatial Fabric (Geofabric) (Bureau of Meteorology, 2012); and (iii) climate grids, which are the basis of the Budyko framework (Budyko, 1974). For purposes of defining the PAE, surface water impacts from longwall mines are assumed to be negligible (although subsidence can potentially have impacts on surface water through disruption to drainage and enhanced recharge) and that the groundwater PAE will capture the affected area along the stream.

Estimates of surface runoff generation from the open-cut mines and related catchments were generated using a spatial implementation of the Budyko framework. Over the long term, the relative proportion of the streamflow generated in a catchment relates to its area and the spatial changes in climate across the catchment (Budyko, 1974; Donohue et al., 2011). Donohue et al. (2007, 2010) provide general introductions to the Budyko framework. The summary presented in this product is from McVicar et al. (2012).

The catchment water balance describes the partitioning of the inward flux, or supply, of water (assumed here to be solely precipitation) into the outward fluxes of water and the within‑catchment storage of water. With respect to streamflow, the water balance is:

|

|

(1) |

Here Q is streamflow at some point in the stream network, and P, AET, and DD represent, precipitation, actual evapotranspiration and deep drainage over the catchment contributing to that point, respectively. They all have the same units (mm a–1). Sw is soil water storage (mm). In unregulated catchments the partitioning of P into Q and AET predominantly depends on the processes that determine AET. In general, AET is limited by either the supply of (i) water or (ii) energy (this can be termed atmospheric evaporative demand (AED) and is commonly represented as potential evapotranspiration (PET)). This means that AET from a catchment can be described as being either ‘water-limited’ or ‘energy-limited’, respectively. This supply-demand limitation is a crucial over-arching framework for understanding catchment hydroclimatology; it does not account for changes in soil properties and assumes groundwater and surface water are in steady-state equilibrium, with groundwater recharge to and discharge from the stream being negligible.

Assuming steady state, Budyko (1974) described a long-term catchment balance using the supply-demand framework (Figure 5). Formally, a water-limited environment occurs when the long-term catchment average AED for water exceeds the supply of water (i.e. P < PET) and the opposite is true for an energy-limited environment (i.e. P > PET). Over large catchments and long timescale, Budyko showed that the evaporative index (ε, the ratio of AET to P) is dependent on the climatic dryness index (Φ, the ratio of PET to P) and closely follows a curvilinear relationship (the ‘Budyko curve’, shown in Figure 5). As water limitation increases (i.e. as one moves to the right in Figure 5), then AET approaches P and Q approaches 0. Conversely, as the water availability increases (i.e. as one moves to the left in Figure 5), AET approaches PET, with a larger fraction of P being partitioned into Q.

Figure 5 The Budyko curve and the supply-demand framework

The Budyko curve (black line) describes the relationship between the long‑term catchment averages of the evaporative index (ε = AET / P) and the dryness index (Φ = PET / P). The horizontal grey line represents the water‑limit, where 100% of P becomes AET, and the diagonal grey line is the energy‑limit, where 100% of AED (i.e. PET) is converted to AET. The green shaded area represents the fraction of P that becomes AET and the blue shaded area represents the fraction of P that becomes Q.

AED = atmospheric evaporative demand, AET = actual evapotranspiration, P= precipitation, PET = potential evapotranspiration, Q = streamflow

Source: McVicar et al. (2012) from Budyko (1974). This figure is not covered by a Creative Commons Attribution licence. © 2012 Commonwealth of Australia.

Using Choudhury’s (1999) formulation of the Budyko curve, with (i) available energy being represented as PET (Donohue et al., 2012) and, (ii) adopting a catchment properties parameter, which alters the partitioning of P between modelled AET and R (runoff), of n = 1.9 (Donohue et al., 2011) and (iii) assuming steady-state conditions, R can be simply calculated as the difference between P and AET:

|

|

(2) |

Note that in the introduction to the Budyko framework, in which the smallest spatial element considered is a subcatchment, Q is used, whereas for spatially explicit modelling using gridded meteorological data the term R is used. These are not identical in meaning and in the Budyko framework there is no routing within a catchment or down the river network. To define the PAE it is the relative proportions of the spatially explicit runoff, R, that are required.

The footprints (areas) of the two open-cut coal mine pits were derived from Landsat-7 ETM+ imagery acquired on 3 December 2012 (path/row is 90/83) (Bioregional Assessment Programme, Dataset 47) and are shown in the inset map of Figure 6. Based on catchment delineation in the Geofabric, four subcatchments were identified as hydrologically connected to the Invincible open-cut coal mine and three subcatchments to the Pine Dale open-cut coal mine (Figure 6). The footprint and subcatchment areas are summarised in Table 7.

Using readily available gridded meteorological datasets of P (Jones et al., 2009) and Penman’s formulation of PET (Donohue et al., 2010), which is fully physically based using a dynamic wind speed (McVicar et al., 2008), Choudhury’s formulation of the Budyko framework was used to model the climatological (1982 to 2010) partitioning of P in AET and R. Figure 7a and Figure 7b show the input meteorological grids used in Choudhury’s formulation of the Budyko framework; the resultant modelled runoff is shown in Figure 7c. To provide a more meaningful illustration of the grid-cell modelling, Figure 8 shows how this aggregates given the surface water network taking into account the catchment topology (i.e. size and spatial relationships) thereby showing the accumulation of flow downstream and the relative differences in streamflow (due primarily to differences in catchment size and climatic conditions). Note the differences in flow scales between the main diagram and Inset (a) and Inset (b).

Surface water catchments used in subsequent analysis are shown in the inset map. Codes have been assigned and are shown in orange (see Table 7).

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46, Dataset 47)

Table 7 Subcatchments connected to the Invincible and Pine Dale open-cut coal mines

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 48); CSIRO (Dataset 49)

Figure 8 Average annual (1982 to 2010) predicted runoff accumulated for the Sydney Basin bioregion

Inset (a) is a close-up of the Western Coalfield; (b) is a close-up of the Southern Coalfield. Only stream segments with greater than 20,000 ML/year are shown; below this threshold, the drainage lines (not streamflow associated with it) are shown.

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 50)

Annual average P, PET and R were calculated for the two open-cut mine areas and associated subcatchments. These are summarised in Table 8 for each mine as the percentage contribution from each area to the total from all subcatchment areas. The Invincible mine footprint contributes less than 1% of the long-term total P, PET and R of the four Invincible subcatchments, and the Pine Dale mine footprint contributes about 0.5% of the long-term P, PET and R of the three Pine Dale subcatchments (Table 8).

Table 8 Annual average water balance components for Invincible and Pine Dale open-cut coal mines, and their related surface water subcatchments

Annual average (1982 to 2010) water balance components are shown for precipitation, potential evapotranspiration (PET calculated with the Penman formulation) and Choudhury’s modelled runoff for the two open-cut mines and each of their related surface water subcatchments. Percentages are calculated relative to the respective mine-subcatchment totals. Definitions for the subcatchment codes are provided in Table 7, and their spatial extents are shown in Figure 6.

Table 9 expresses the P, PET and R contributions from the Invincible mine footprint as percentages of total P, PET and R with increasing contributing area. Within the smallest subcatchment in which it is located (Inv_1), the Invincible open-cut mine contributes 6.25% of runoff; moving down catchment and the addition of subcatchment Inv_2, the mine contribution to total runoff decreases to 2.33%; with the addition of Inv_3, this reduces to 1.47%; and then to 0.47% when subcatchment Inv_4 is included. Generally, changes in runoff that are less than about 10% of the long-term average are difficult to detect given the large variability in runoff response, and changes of less than 5% of the total runoff are beyond detection level. Any changes to surface water flows downstream of the outlet to subcatchment Inv_2 are predicted to be negligible, hence the catchments of Inv_1 and Inv_2 are used to define the surface water PAE for the Invincible open-cut mine.

Table 9 Percentage contribution of the Invincible open-cut mine footprint to increasing subcatchment areas

Annual average (1982 to 2010) water balance components for precipitation, potential evapotranspiration (calculated with the Penman formulation) and Choudhury’s modelled runoff. The percentage contributions of the mine footprint relative to the subcatchments, indicated by the denominator, are reported. Definitions for the subcatchment codes are provided in Table 7, and their locations are illustrated in Figure 6 (specifically the inset map).

Table 10 provides a similar analysis for Pine Dale open-cut mine. The area occupied by this mine contributes only 0.95% of the runoff of subcatchment PD_1. This is below the 5% threshold for detection of change (as discussed for Invincible open-cut mine), thus subcatchment PD_1 is used to define the surface water PAE for the Pine Dale open-cut mine.

Table 10 Percentage contribution of the Pine Dale open-cut mine footprint to increasing subcatchment areas

Annual average (1982 to 2010) water balance components for precipitation, potential evapotranspiration (calculated with the Penman formulation) and Choudhury’s modelled runoff. The percentage contributions of the mine footprint relative to the subcatchments, indicated by the denominator, are reported. Definitions for the subcatchment codes are provided in Table 7, and their locations are illustrated in Figure 6 (specifically the inset map).

The total surface water PAE is shown in Figure 6 and comprises Inv_1, Inv_2 and PD_1.

1.3.1.3.3 Surface water – groundwater considerations: longwall mines

To model impacts upon surface water from longwall coal mines, an approach was developed to define the PAE based on surface water – groundwater connectivity considerations. Generally, watercourses in the Sydney Basin bioregion are considered to be gaining streams, which means there is a flow of groundwater to the stream. Jankowski (2007, 2009) has identified some general characteristics of how watercourses near longwall mining operations are affected. In undisturbed systems, the direction of groundwater flow is typically towards the stream as baseflow, with discharges coming from springs or through the streambed in areas of significant vertical faulting and fracturing. During longwall mining operations, impacts can include changes to the strength and direction of the local groundwater gradient to the stream, with consequent flow changes. Structural changes that increase fracturing of bedrock under the stream and more widely can lead to reductions in surface water flow to the stream and increased losses through the streambed through new or expanded fracture zones. Given sufficient changes, the stream can become disconnected from the underlying groundwater, leading to a reversal of hydraulic gradients and the stream losing water to groundwater. Structural alterations from mining operations increase the complexity of the flow paths controlling surface water – groundwater interactions. Furthermore, they almost exclusively result in decreased flow in creeks and potentially less groundwater discharge to other creeks in the immediate surface water catchment. It is not known the extent to which local-scale streamflow losses impact river flow in increasingly higher order streams down the network, but they must be considered as potentially affecting streamflow downstream from mining operations.

As there are several recorded cases of watercourses (rivers and creeks) and water bodies (upland swamps) being drained following longwall mining operations in the Southern Coalfield area of the Sydney Basin bioregion (Krogh, 2007; McNally and Evans 2007; and the references therein), a conservative approach has been adopted to the calculation of this component of the PAE and it is assumed that all groundwater and surface water flowing from the catchment is intercepted by longwall mining activity. While this assumption almost certainly exaggerates the potential impact of longwall coal mining in many cases, it was used to define an upper bound for calculations and to ensure that this component of defining the PAE will not result in potentially affected assets being excluded. The Budyko framework (introduced above) was used to quantify the volume of runoff intercepted by each mine and then calculate the percentages of total runoff it represented for increasing catchment areas, as was done in Section 1.3.1.3.2. When the contribution from the 100% perturbed mine-containing catchment was less than 5% of the subcatchment total, it was assumed that its contribution was negligible. The threshold follows the same logic as presented for the surface water PAE calculations. For those subcatchments in which the mine site contribution to runoff was deemed significant, a buffer was put around the main channel running through the subcatchments and this was used to define that part of the PAE where surface water – groundwater interactions could potentially be affected by mining developments in the bioregion. The locations of subcatchments for each mine in the Western and Southern coalfields are shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10 respectively.

Airly, Angus Place, Cullen Valley, Clarence and Springvale underground coal mines are shown. Catchments are numbered in order of increasing catchment area, with ‘0’ always assigned to the first order stream catchment in which the mine is located.

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46)

Tahmoor, Appin – West Cliff, Dendrobium, Russell Vale and Wongawilli underground coal mines are shown. Catchments are numbered in order of increasing catchment area, with ‘0’ always assigned to the first order stream catchment in which the mine is located.

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46)

Table 11 summarises subcatchment codes, subcatchment areas, and average annual runoff from each area, expressed as a percentage of total average annual runoff for the five underground coal mines in the Western Coalfield around Lithgow. The relative runoff contributions with increasing subcatchment level are provided in Table 12. The subcatchment level at which the runoff contribution from the mine was less than 5% of total runoff was:

- Airly: Level 3 (i.e. L1+L2+L3)

- Cullen Valley: Level 2

- Angus Place: Level 3

- Springvale: Level 1

- Clarence: Level 2.

There are six underground mines in the Southern Coalfield. Appin and West Cliff mines are located in adjacent first-order surface water catchments and were grouped together for this analysis. Details of subcatchment codes, areas and percentage runoff contributions are summarised in Table 13. For mines in the Southern Coalfield, the relative contribution of runoff from the subcatchment containing the mine was less than 5% for the following mine-subcatchment levels (Table 14):

- Appin + West Cliff: Level 3

- Russell Vale: Level 3

- Dendrobium: Level 1

- Wongawilli: Level 2.

Table 11 Details of subcatchments around the Western Coalfield underground coal mines

The annual average runoff calculation is relative to the highest level shown for each mine and results are not nested.

‘na’ means not applicable as not all mines required analysis to the fifth level. The mines are reported from north to south. Locations of subcatchments for each mine are shown in Figure 9.

Table 12 Relative runoff contribution of Western Coalfield catchments containing an underground coal mine in wider regional context

‘na’ means not applicable as not all mines required analysis to the fifth level. The mines are reported from north to south. Locations of subcatchments for each mine are shown in Figure 9.

Table 13 Details of subcatchments around the underground coal mines in the Southern Coalfield

The annual average runoff calculation is relative to the highest level shown for each mine and results are not nested.

‘na’ means not applicable as not all mines required analysis to the fifth level. The mines are reported from north to south. Locations of subcatchments for each mine are shown in Figure 10.

Table 14 Relative runoff contribution of Southern Coalfield catchments containing one or more underground coal mines when placed in wider regional context

‘na’ means not applicable as not all mines required analysis to the fifth level. The mines are reported from north to south. Locations of subcatchments for each mine are shown in Figure 10.

The analysis for the Tahmoor mine was slightly greater than the 5% threshold and required further investigation. To ensure that the mine-catchment contribution was less than 5% of the regional runoff contribution, an additional surface water catchment for the Tahmoor mine needed to be defined. However, the next subcatchment level for the Tahmoor mine includes the Dendrobium mine catchment, so in this additional analysis, the two mine catchments were considered together (Figure 11). Details of the subcatchments are reported in Table 15 and their relative runoff contributions with increasing subcatchment level are provided in Table 16. Results show that at subcatchment level 1, the combined runoff contribution from Tahmoor and Dendrobium mines is below the 5% threshold. This concludes the first step of the analysis, to identify which catchments should be included in the PAE based on considerations of surface water – groundwater connectivity.

Figure 11 Subcatchments definition for the merged Tahmoor and Dendrobium analysis

Catchments are numbered in order of increasing catchment area, with ‘0’ always assigned to the first order stream catchment in which the mine is located.

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46)

Table 15 Details of subcatchments around the Tahmoor and Dendrobium underground coal mines

|

Subcatchment level |

Subcatchment codes |

Area (km2) |

Annual average runoff (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Containing the Mines |

Tahmoor+Dendrobium |

7.97 |

0.93% |

|

First level |

TD_1 |

827.80 |

92.37% |

|

Second level |

TD_2 / |

175.22 |

6.70% |

The annual average runoff calculation is relative to the highest level shown for each mine and results are not nested.

Table 16 Relative runoff contributions from Tahmoor and Dendrobium underground coal mines in the wider catchment context

|

Mine / level(s) |

Tahmoor + Dendrobium annual average runoff (%) |

|---|---|

|

Mine / L1 |

1.00 |

|

Mine / (L1 + L2) |

0.93 |

In the second and final step, the distance of the buffer either side of the main channels, in which the groundwater and surface water are likely to be connected, was defined. Most of the main channels defining locations of potential surface water – groundwater connectivity are already contained within the groundwater PAE (Figure 14). Only around the Angus Place mine, and to lesser extents the Clarence, Cullen Valley and Appin-West Cliff mines, is it possible that surface water – groundwater connectivity may extend beyond the groundwater PAE. Thus the valley floor characteristics of the valleys around these mines, using the MrVBF (Multi-resolution Valley Bottom Flatness) terrain analysis product (Gallant and Dowling, 2003), informed the delineation of the buffer. Figure 12 shows flat areas identified along streams around the Angus Place mine. A maximum buffer width of 500 m was determined to be sufficiently wide enough to accommodate the full extent of flat areas. Thus, a 500 m buffer was applied to all main channels in catchments identified in the previously documented Budyko analysis for the longwall mines. The final result is presented in Figure 13.

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43, Dataset 51); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46); CSIRO (Dataset 52)

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46)

1.3.1.3.4 The final preliminary assessment extent

The final PAE of the Sydney Basin bioregion was defined as the union of the groundwater PAE, surface water PAE and surface water – groundwater connectivity PAE. The overlay of these three components is shown in Figure 14 and the unified PAE boundary in Figure 15. The Sydney Basin bioregion covers about 24,606 km2, of which the PAE covers about 5,398 km2. The PAE comprises two disconnected components: one in Western Coalfield in the vicinity of Lithgow (2522 km2); and the second in the Southern Coalfield centred on Wollongong (2876 km2). It is in the PAE that geospatial referenced lists of water-dependent assets will be identified.

Data: Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44); Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 46)

Figure 15 Preliminary assessment extent (PAE) of the Sydney Basin bioregion

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 53); Geoscience Australia (Dataset 43); NSW Trade and Investment (Dataset 44)