- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

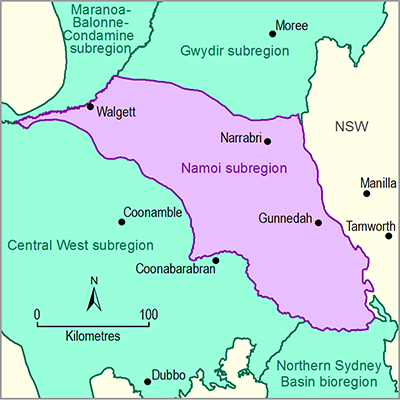

- Namoi subregion

- 2.3 Conceptual modelling for the Namoi subregion

- 2.3.3 Ecosystems

- 2.3.3.2 Landscape classification

Twenty-nine landscape classes were derived using the approach detailed in Section 2.3.3.1. These 29 landscape classes were allocated to one of six landscape groups based on broad-scale distinctions in their water dependency and association with floodplain/non-floodplain environments, GDEs and remnant/human-modified habitat types (Table 6). The 29 landscape classes are presented in Table 7, Table 8 and Table 9 and are based on their spatial attribution as either polygons, lines or points as defined in Table 5.

Most of the PAE (59.3%) is classified in the ‘Human-modified’ landscape group, which includes agricultural, urban and other intensive land uses (Table 7). Among those areas classified as remnant vegetation, the majority (24.2% of the PAE) fell into the ‘Grassy woodland’ landscape class (‘Dryland remnant vegetation’ landscape group) (Table 7 and Figure 20); they are assumed to be non-water dependent because they do not intersect floodplain, wetland or GDE features. The ‘Floodplain or lowland riverine’ landscape group covers 6.2% of the PAE. Of the remaining non-floodplain landscapes, GDEs cover 9.1% of the PAE, with ‘Grassy woodland GDE’ making up the vast majority of these. A very small portion of this non-floodplain environment (0.5% of the PAE) contains ‘Rainforest’ or ‘Rainforest GDE’ landscape classes (Table 7 and Figure 20).

Table 7 Land area and proportion of polygon landscape classes in the Namoi preliminary assessment extent

aPunctuation and typography appear as generated by the landscape classification.

bThese riverine features were mapped as polygons in the source datasets.

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem, PAE = preliminary assessment extent

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9)

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9), Bureau of Meteorology (Dataset 10)

The ‘Non-floodplain or upland riverine’ landscape group made up the largest proportion of the stream network (63.8%) (Table 7, Table 8 and Figure 21). Among the landscape classes within the ‘Non-floodplain or upland riverine’ landscape group, most belong to the ‘Temporary upland stream’ landscape class (Table 8). The lowland riverine streams are also predominantly classified as ‘temporary’ and only approximately 5% of these streams are associated with GDEs (Table 8).

Of the 22 springs classified within the Namoi PAE, 7 are associated with the GAB aquifers (Table 9 and Figure 22).

Table 8 Length of stream network classes in the Namoi preliminary assessment extent

aPunctuation and typography appear as generated by the landscape classification.

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9)

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9), Bureau of Meteorology (Dataset 10)

Figure 22 'Springs' landscape group across the Namoi preliminary assessment extent

GAB = Great Artesian Basin

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9), Bureau of Meteorology (Dataset 10)

Table 9 Landscape classes in the ‘Springs’ landscape group in the Namoi preliminary assessment extent

|

Landscape groupa |

Landscape class number |

Landscape classa |

Total count |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Springs |

21 |

GAB springs |

7 |

|

22 |

Non-GAB springs |

15 |

|

|

Total |

22 |

aPunctuation and typography appear as generated by the landscape classification.

GAB = Great Artesian Basin

Table 10 Location, associated communities, threatened ecological communities, water dependency and nature of water dependency for each landscape group

|

Landscape group |

Location |

Associated communities |

Listed ecological communities (EPBC Act) |

Nature of dependency |

Water sources and water regime (spatiala, temporalb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Floodplain or lowland riverine |

Quaternary alluvial systems |

|

|

|

Surface water (regional, episodic) and groundwater (landscape, aseasonal/intermittent) |

|

Non-floodplain or upland riverine |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Human-modified |

Irrigated agriculture concentrated around the Narrabri and Gunnedah formations and other floodplain systems |

|

na |

|

Rainfall (local, intermittent); surface water (local-regional, temporary-near-permanent); groundwater (local-regional, temporary-near-permanent) |

|

Rainforest |

Small isolated pockets along creek lines and at higher elevations in east of the preliminary assessment extent |

|

Semi-evergreen vine thickets of the Brigalow Belt (North and South) and Nandewar Bioregions |

|

Rainfall (local, intermittent); surface water (local-regional, temporary-near-permanent); groundwater (local-regional, temporary-near-permanent) |

|

Dryland remnant vegetation |

Upland areas (excluding floodplains and areas mapped as GDEs) |

|

|

Reliant on locally stored soil water |

Rainfall and runoff, (localised, temporary) |

|

Springs |

Occur across different landscapes including break of slopes, dissected volcanic formations, tablelands and alluvial plains |

|

na |

Maintained and defined by groundwater flow patterns from several different hydrogeologies including sandstones and volcanic basalts |

Groundwater (ranging from localised to regional, both temporary and permanent) |

aSpatial scale refers to the flow system and its predominant pattern at local (100 to 104 m2), landscape (104 to 108 m2) or regional (108 to 1010 m2).

bTemporal scale of the water regime refers to the timing and frequency of the reliance on a particular water source.

EPBC Act = Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation 1999, GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem, na = not applicable

2.3.3.2.1 ‘Floodplain or lowland riverine’ landscape group

Floodplains can be defined broadly as a collection of landscape and ecological elements exposed to inundation or flooding along a river system (Rogers, 2011). The floodplain landscapes of the Namoi PAE are predominantly lowland-dryland systems incorporating a range of wetland types such as riparian forests, marshes, billabongs, tree swamps, anabranches and overflows (Rogers, 2011). Landscape classes in the ‘Floodplain or lowland riverine’ landscape group occupy a land area of approximately 6% of the Namoi PAE, and make up around a quarter of the entire length of the stream network (Table 7 and Table 8). Figure 23 is an example of the distribution of landscape classes along typical floodplain areas along the Namoi River.

A riparian zone that fringes the river channel typifies floodplain landscapes along major rivers in the PAE such as the Namoi River. This riparian environment is represented by the ‘Floodplain riparian forest’ and ‘Floodplain riparian forest GDE’ landscape classes and is dominated by tree species such as river red gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and river oak (Casuarina cunninghamiana; Figure 25) (Benson et al., 2010). The methodology used to ascertain groundwater dependency in the NSW GDE dataset (NSW Office of Water, Dataset 6) assumes that all riparian areas are groundwater dependent, thus most of these riparian landscapes were classified as ‘Floodplain riparian forest GDE’ (Table 7) (NSW DPI, 2016).

Adjacent to the riparian zone is the back plain environment, representing the transition between the frequently flooded river channel and the upland environment. This back plain environment contains floodplain woodlands and various types of wetlands with varying degrees of groundwater dependency (Figure 24 and Table 10) (Holloway et al., 2013). The back plain environment tends to be dominated by woodland species such as poplar box (Eucalyptus populnea), black box (Eucalyptus largiflorens), coolibah (Eucalyptus coolabah), river coobah (Acacia stenophylla) and other Eucalyptus spp., shrubs and grasses (most commonly plains grass – Austrostipa aristiglumis) (see Figure 25 for an example) (Eco Logical, 2009). Landscape classes occurring in the back plain environment include ‘Floodplain grassy woodland’ and ‘Floodplain grassy woodland GDE’. Flooding frequency, duration and depth tend to be reduced for the floodplain wetland landscape classes that tend to have a ‘temporary’ water regime (Figure 24 and Table 10).

Elements of the ‘Floodplain grassy woodland GDE’ landscape class tend to be interspersed along the riparian and back plain environments and groundwater use is influenced by access (depth to groundwater) and salinity (Table 10). Alluvial aquifers form in deposited sediments such as gravel, sand, silt and/or clay within the river channels or on the floodplain. Water is stored and transmitted to varying degrees through inter-granular voids; this means that aquifers are generally unconfined and shallow, and have localised flow systems (DSITI, 2015). Groundwater expressed at the surface supports ecosystems occupying drainage lines, riverine water bodies, lacustrine and palustrine wetlands.

Several listed ecological communities are found in the ‘Floodplain or lowland riverine’ landscape group areas including the ‘Coolibah - Black Box Woodlands of the Darling Riverine Plains and the Brigalow Belt South Bioregions’ (Table 10), listed under the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9)

The arrows indicate the direction of water movement, with the dashed arrow line indicating variable groundwater leakage and the crossed (red) arrow line indicating negligible groundwater movement. The blue dashed horizontal line indicates the position of the watertable within the cross-section.

Source: DEHP (2015a)

(a) ‘Permanent lowland stream’ landscape class and adjacent ‘Floodplain riparian forest’ landscape class, (b) ‘Floodplain grassy woodland’ landscape class approximately 100 m from the river

Credit: Bioregional Assessment Programme, Patrick Mitchell (CSIRO), January 2016

2.3.3.2.2 ‘Non-floodplain or upland riverine’ landscape group

The landscape classes in the ‘Non-floodplain or upland riverine’ landscape group include upland streams and wetlands that are not associated with floodplains. ‘Non-floodplain wetland’ and ‘Non-floodplain wetland GDE’ landscape classes on shrink-swell cracking clays of low permeability sometimes form ‘tank gilgai’ (meaning ‘small waterhole’ wetlands) and are common within the Pilliga Nature Reserve (Bell et al., 2012). These temporary wetlands are essentially small depressions within the Cenozoic clay deposits that are interspersed with mounds and depressions over relatively small distances (approximately 2 m; Chertkov, 2005). Spatial variation in infiltration occurs as these clays swell when wet, causing cracks to close and water to pool on the surface (Chertkov, 2005). The wetlands tend to occur within a mosaic of woodlands and shrublands largely dominated by buloke (Allocasuarina luehmannii), Eucalyptus chloroclada, Eucalyptus pilligaensis, Eucalyptus sideroxylon and Melaleuca densispicata (Benson et al., 2010). They are commonly fringed by buloke and various sedge, rush and other herbaceous plant communities (Bell et al., 2012). The nature of wet and dry phases within these wetlands is determined by localised runoff from rainfall, which means that their dependency on flow systems at larger scales is likely to be negligible (Table 10).

Figure 26 A dry gilgai wetland near the Pilliga Scrub in the Namoi subregion

Credit: Bioregional Assessment Programme, Patrick Mitchell (CSIRO), January 2016

Goran Lake is a different type of non-floodplain wetland in the southern part of the PAE and is listed in A directory of important wetlands (Environment Australia, 2001) and the asset register for the BA of the Namoi subregion (Bioregional Assessment Programme, Dataset 8). This wetland is characterised as having a large internal drainage basin (>6000 ha) and historically has been an ephemeral system (filled once in 20 years) until recent diversions of two creek systems have shifted the lake towards semi-permanence (Environment Australia, 2001). The lake supports several ground cover species including nardoo (Marsilea drummondii), narrow-leaved cumbungi (Typha domingensis) and lignum (Muehlenbeckia florulenta), and a narrow band of riparian woodland species (e.g. river red gum) (Environment Australia, 2001).

Terrestrial GDEs (those that rely on the subsurface presence of groundwater) and surface GDEs (those that rely on the surface expression of groundwater) across the non-floodplain areas of the PAE are diverse and are represented by ‘Non-floodplain wetland GDE’, ‘Grassy woodland GDE’, ‘Upland riparian forest GDE’, ‘Temporary upland stream GDE’, and ‘Permanent upland stream GDE’ landscape classes. For example, the ‘Grassy woodland GDE’ landscape class is found along the eastern portion of the Namoi PAE and may be associated with basalt or permeable rock types where groundwater is transmitted and stored through fractures, inter-granular spaces or weathered zones, and is typically discharged to the surface at contact zones between two rock types (Figure 28 and Figure 29) (DSITI, 2015). The other significant expanse of the ‘Grassy woodland GDE’ landscape class is found in the Pilliga Nature Reserve. This large remnant of vegetation was once grazed and selectively harvested for timber (ironbark sleepers and cypress pine sawlogs) until being a reserve in the latter 20th century (Norris, 1996). The underlying geology is dominated by the Pilliga Sandstone and other sedimentary outcrop areas (Rolling Downs and Blythesdale formations). Although NSW Office of Water (NSW Office of Water, Dataset 6) and GDE Atlas (Bioregional Assessment Programme, Dataset 7) mapping show a significant extent of this landscape class, limited ground-validated information exists on the nature of the vegetation’s relationship with groundwater across the landscape. The most likely areas where there is a high likelihood of groundwater dependency would be along drainage lines and riverine landscapes (i.e. Bohena Creek, Figure 27) and where groundwater might be expressed at the surface from zones of rejected recharge (see Table 10).

Figure 27 Bohena Creek and riparian vegetation in the Pilliga Nature Reserve

Credit: Bioregional Assessment Programme, Patrick Mitchell (CSIRO), January 2016

Figure 28 Non-floodplain groundwater-dependent ecosystems in the Namoi preliminary assessment extent

Non-floodplain groundwater-dependent ecosystems (GDEs) include remnant vegetation (‘Grassy woodland GDE’ landscape class), wetland (‘Non-floodplain wetland GDE’ landscape class) and riverine GDEs (‘Permanent upland stream GDE’ and ‘Temporary upland stream GDE’ landscape classes).

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 9)

These systems are typical of those landscapes that form on basaltic (volcanic) rocks in the east of the Namoi subregion.

GDE = groundwater-dependent ecosystem

Source: DEHP (2015b)

2.3.3.2.3 ‘Springs’ landscape group

GAB springs in the Namoi subregion are surface expressions of groundwater sourced from aquifers contained in the Jurassic and Cretaceous sedimentary sequences associated with the GAB (Habermehl, 1982). Spring ecosystems contain many locally endemic species and plant communities and have significant ecological, economic and cultural values (Fensham and Fairfax, 2003). In the Namoi PAE there are no artesian spring communities listed under the EPBC Act, but there is one artesian spring community listed under NSW’s Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 known to occur on the Liverpool Plains. Several of the springs identified in the ‘GAB springs’ landscape class are likely to be ‘recharge’ springs. Recharge springs form where the sediments that make up the aquifers of the GAB have surface expressions and tend to be situated within the recharge zones of the eastern margin of the GAB (Figure 30) (Fensham and Fairfax, 2003), such as the sandstone layers underlying the Pilliga Scrub (NSW Department of Water and Energy, 2009).

Springs in the ‘Non-GAB springs’ landscape class occur in the groundwater management area outside of the GAB (Figure 22). These springs are located in groundwater aquifers located within the Oxley Basin, New England Fold Belt, Peel Valley Fractured Rock and Warrumbungle Basalt.

Source: DEHP (2013)

2.3.3.2.4 ‘Rainforest’ landscape group

The ‘Rainforest’ landscape group is distinguished primarily by its vegetation structure and composition. Rainforests were identified based on Keith’s vegetation classification system, where ‘vegetation formation’ is the top level of the hierarchy, and included the ‘rainforest’ and ‘wet sclerophyll’ vegetation formations (Keith, 2004). The ‘wet sclerophyll’ vegetation formation makes up less than 300 ha of the Namoi PAE, whereas most of the ‘Rainforest’ landscape group comprises the ‘rainforest’ vegetation formation making up approximately 20,000 ha of the Namoi PAE. ‘Rainforests’ are defined as forests with a closed canopy generally dominated by non-eucalypt species with soft, horizontal leaves, however various eucalypt species may be present as emergents (Keith, 2004). The ‘Rainforest’ landscape group is predominately ‘Dry rainforest’ or ‘Western vine thickets’ (both threatened vegetation classes in NSW). They tend to occupy upland riparian habitats and higher elevations in the eastern and southern regions of the Namoi PAE within sheltered positions areas such as Mount Kaputar (Figure 20) (Benson et al., 2010). They are predominately associated with basaltic substrates, but also riverine alluvium, sandstones and granites. The water dependency of the ‘Rainforest’ landscape group is likely to be mostly from localised surface runoff, and in the case of ‘Rainforest GDE’ landscape class, from groundwater sourced from localised discharge from fractured or porous substrates (see Figure 29 for a conceptual overview).

2.3.3.2.5 ‘Human-modified’ landscape group

Most of the PAE (59%) is dominated by human-modified landscapes used for agricultural production, mining and urban development (Table 7). The water dependency of the landscape classes derived from this landscape group ranges from a heavy dependence on groundwater and surface water extracted from nearby aquifers and streams (e.g. ‘Intensive uses’ and ‘Production from irrigated agriculture and plantations’ landscape classes), through to dryland cropping and grazing reliant on incident rainfall and local surface water runoff (e.g. ‘Production from dryland agriculture and plantations’ landscape class) (Table 10). Deep-rooted vegetation, such as tree plantations, may tap into groundwater within certain landscapes. Intensive areas, such as townships, often have a strong reliance on groundwater and surface water via bores and river offtakes.

Credit: Bioregional Assessment Programme, Patrick Mitchell (CSIRO), January 2016

2.3.3.2.6 ‘Dryland remnant vegetation’ landscape group

The ‘Dryland remnant vegetation’ landscape group represents a large component of those landscapes classified as ‘remnant’ in the NSW regional native vegetation mapping (SEWPaC, Dataset 4). The associated communities are highly variable and cover many different types of woodland, shrubland and grassland (Table 10, Figure 32). The ‘White Box-Yellow Box-Blakely's Red Gum Grassy Woodland and Derived Native Grassland’ threatened ecological community listed under the EPBC Act occurs across a large part of the Namoi PAE (excluding eastern regions and Pilliga Nature Reserve) and is largely classified as ‘Grassy woodlands’ as well as being distributed across those landscape classes thought to be water dependent (e.g. occurring on floodplains and groundwater dependent). The term ‘dryland’ implies that this landscape group is reliant on incident rainfall and local runoff and does not include features in the landscape that have potential hydrological connectivity to surface or groundwater features.

(a) white cypress pine – white box woodland (‘Grassy woodland’ landscape class) in the Doona State Forest, (b) narrow-leaved ironbark – forest oak – white cypress pine woodland in the Pilliga Nature Reserve

Credit: Bioregional Assessment Programme, Patrick Mitchell (CSIRO), January 2016

Product Finalisation date

- 2.3.1 Methods

- 2.3.2 Summary of key system components, processes and interactions

- 2.3.3 Ecosystems

- 2.3.4 Coal resource development pathway

- 2.3.5 Conceptual modelling of causal pathways

- Citation

- Acknowledgements

- Currency of scientific results

- Contributors to the Technical Programme

- About this technical product