- Home

- Assessments

- Bioregional Assessment Program

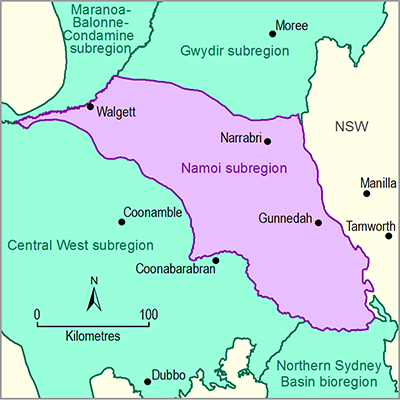

- Namoi subregion

- 5 Outcome synthesis for the Namoi subregion

- What are the potential hydrological changes?

Key finding 2

The zone of potential hydrological change (Figure 1 and Box 4) covers an area of 7014 km2, including 5521 km of streams. This represents about 20% of the area in the entire Namoi assessment extent.

Outside this zone, potential changes to water quantity and availability due to additional coal resource development are very unlikely.

Groundwater

It is very unlikely that baseline drawdown due to coal mining extends more than about 10 km from any mine (Figure 8). Additional drawdown due to the Narrabri Gas Project is estimated to extend over a much larger area but is generally lower in magnitude compared to drawdown due to the mines (Figure 9). Key finding 3

Results are reported for the regional watertable, which comprises the alluvial aquifer as well as weathered and fractured rock aquifers. The year when maximum change is attained varies throughout the subregion. It is most likely to be during the decades after mining activity ceases, and occurs later with increasing distance from mine tenements (Janardhanan et al., 2018).

The area with at least a 5% chance of greater than 0.2 m drawdown due to baseline development is 479 km2; baseline coal mines are sufficiently separated so that there is no overlap of drawdown with neighbouring baseline mines (Figure 8). The area with the same chance of this drawdown due to additional coal resource development is 2299 km2 (Figure 9) of which 287 km2 is alluvium, representing 8% of the upper Namoi alluvium and 0.01% of the lower Namoi alluvium (Table 8 in Herr et al. (2018a)). Key finding 4

Drawdown due to additional coal resource development covers a much larger area compared to baseline drawdown, although, as for baseline mines, drawdown due to additional mines is very unlikely to extend more than about 10 km from the mine. In some cases, however, drawdown does overlap due to multiple developments that are nearby. These areas have potential cumulative impacts:

- Drawdown due to Narrabri South overlaps with drawdown due to the baseline Narrabri North Mine, as well as that due to the Narrabri Gas Project.

- East of these developments, drawdown due to the Maules Creek Mine overlaps with drawdown due to the baseline Boggabri Coal Mine, the Boggabri Coal Expansion Project, the baseline Tarrawonga Mine and the Tarrawonga Coal Expansion Project.

- South of these mines, drawdown due to the Vickery Coal Project overlaps with drawdown due to the baseline Rocglen Mine.

- Modelling also suggested potential overlap between the Watermark Coal Project and the now-abandoned Caroona Coal Project.

It is very likely that 156 km2 will experience at least 0.2 m of drawdown due to additional coal resource development, but very unlikely that this will extend beyond 2299 km2. An area of 99 km2 is very likely to experience at least 5 m of drawdown due to additional coal resource development, but it is very unlikely that more than 520 km2 will experience more than 5 m of drawdown (Table 6 in Herr et al. (2018a)).

Baseline drawdown is the maximum difference in drawdown under the baseline relative to no coal resource development (Box 3). Results are shown as percent chance of exceeding drawdown thresholds (Box 5). These appear in Herr et al. (2018a) as percentiles. Areas reported for drawdown exclude the mine pit exclusion zones.

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 5)

Additional drawdown is the maximum difference in drawdown between the coal resource development pathway and baseline, due to additional coal resource development (Box 3). Results are shown as percent chance of exceeding drawdown thresholds (Box 5). These appear in Herr et al. (2018a) as percentiles. Areas reported for drawdown exclude the mine pit exclusion zones.

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 5)

Drawdown is a lowering of the groundwater level that is a result of, for example, pumping. The groundwater model predicted drawdown under the coal resource development pathway and drawdown under the baseline (baseline drawdown). The difference in drawdown between the coal resource development pathway and baseline futures (referred to as additional drawdown) is due to additional coal resource development. In a confined aquifer, drawdown relates to a change in water pressure and does not necessarily translate to changes in depth to the watertable. The maximum drawdown over the course of the groundwater model simulation (from 2013 to 2102) is reported for each 1 km2 grid cell, and occurs at different times across the area assessed. It is not expected that the year of maximum baseline drawdown coincides with the year of maximum additional drawdown. Therefore, simply adding the two figures will result in an amount of drawdown that is not likely to eventuate. Close to open-cut mines, confidence in the results of the groundwater model is very low because of the very steep hydraulic gradients at the mine pit interface. As a result, a mine pit exclusion zone was defined. Groundwater drawdown within this 116 km2 zone was not used in the assessment of ecological impacts. The modelling included coal seam gas depressurisation and mine dewatering, but it did not differentiate the individual effects of these variables on drawdown. Box 3 Calculating groundwater drawdown

Box 4 The zone of potential hydrological change

A zone of potential hydrological change (Figure 1) was defined to rule out potential impacts in areas outside the zone. It is a combination of the groundwater zone of potential hydrological change and the surface water zone of potential hydrological change (see Section 3.3.1 in Herr et al. (2018a)). These zones were defined using hydrological response variables, the hydrological characteristics of the system that potentially change due to coal resource development – for example, groundwater drawdown or the number of low-flow days.

The groundwater zone is the area with at least a 5% chance of greater than 0.2 m drawdown in the near-surface aquifer (Box 3) due to additional coal resource development.

The surface water zone contains those river reaches where there is at least a 5% chance that a change in any one of nine surface water hydrological response variables exceeds specified thresholds (see Table 4 in Herr et al. (2018a)). The surface water zone also includes those streams that flow through the groundwater zone of potential hydrological change where there was insufficient data to enable surface water modelling.

Water-dependent ecosystems and ecological assets outside of this zone are very unlikely to experience any hydrological change due to additional coal resource development. Within the zone, potential impacts may need to be considered further. This assessment used regional-scale receptor impact models (Box 8) to translate predicted changes in hydrology within the zone into a distribution of ecological outcomes that may arise from those changes. Finer-scale assessments may help to account for local conditions.

The chart on the left shows the distribution of results for drawdown in one assessment unit, obtained from an ensemble of thousands of model runs that use many sets of parameters. These generic results are for illustrative purposes only.

The models used in the assessment produced a large number of predictions of groundwater drawdown and changes in streamflow rather than a single number. This results in a range or distribution of predictions, which are typically reported as probabilities – the percent chance of something occurring (Figure 10). This approach allows an assessment of the likelihood of exceeding a given magnitude of change, and underpins the assessment of risk. Hydrological models require information about physical properties, such as the thickness of geological layers and how porous aquifers are. Because it is unknown how these properties vary across the entire assessment extent (both at surface and at depth), the hydrological models were run thousands of times using different sets of values from credible ranges of those physical properties each time. The model runs were optimised to reproduce historical observations, such as groundwater level and changes in water movement and volume. A narrow range of predictions indicates more agreement between the model runs, which enables decision makers to anticipate potential impacts more precisely. A wider range indicates less agreement between the model runs and hence more uncertainty in the outcome. The distributions created from these model runs are expressed as probabilities that hydrological response variables (such as drawdown) exceed relevant thresholds, as there is no single ‘best’ estimate of change. In this assessment, the estimates of drawdown or streamflow change are shown as a 95%, 50% or 5% chance of exceeding thresholds. Throughout this synthesis, the term ‘very likely’ is used to describe where there is a greater than 95% chance that the model results exceed thresholds, and ‘very unlikely’ is used where there is a less than 5% chance. While models are based on the best available information, if the range of parameters is not realistic, or if the modelled system does not reflect reality sufficiently, these modelled probabilities might vary from the changes that occur in reality. These regional-level models provide a range of evidence to rule out potential cumulative impacts due to additional coal resource development in the future. Figure 11 Key areas for reporting probabilistic results The assessment extent was divided into smaller square assessment units and the probability distribution (Figure 10) was calculated for each. In this synthesis, results are reported with respect to the following key areas (Figure 11):Box 5 Understanding probabilities

Surface water

The zone of potential hydrological change in the Namoi subregion includes 5521 km of stream network. Of this, 3629 km (or 66%) are potentially impacted but not quantified, either because of their proximity to the mines or due to difficulties in extrapolating results (Aryal et al., 2018a). Potential changes in these streams cannot be ruled out.

The zone was defined by ten hydrological response variables (Box 4). This synthesis summarises the maximum modelled changes in three hydrological response variables that were used to characterise flows for the impact and risk analysis:

- zero-flow days, which are sensitive to both the interception of surface runoff and the cumulative impact of groundwater drawdown on baseflow over time

- high-flow days, which are more sensitive to interception of surface runoff (Aryal et al., 2018a)

- annual flow, which is also more sensitive to interception of surface runoff.

Changes in other hydrological response variables are available on the BA Explorer at www.bioregionalassessments.gov.au/explorer/NAM/hydrologicalchanges.

Regional-scale modelling indicated that changes in the streamflow of the Namoi River are minimal. However, from the streams where hydrological modelling was possible, Back Creek, Merrygowen Creek and Bollol Creek (Figure 3 and Figure 12) are very likely to experience changes in their streamflow, particularly in the number of zero-flow days. Key finding 5

Most of these creeks have catchment areas much less than 100 km2 and effects are localised.

Zero-flow days

Surface water modelling quantified the annual change in the number of zero-flow days due to additional coal resource development for 1892 km of the 5521 km of streams in the zone of potential hydrological change.

The modelling indicated that it is very unlikely that more than 1678 km of the modelled streams will experience more than an additional 3 zero-flow days per year (see Table 9 in Herr et al. (2018a)). There is a 5% chance that 276 km of modelled streams in the zone will experience 20 or more additional zero-flow days per year, and a 5% chance that 31 km of these streams will experience 200 or more additional zero-flow days per year in the year in which maximum change occurs (see Table 9 in Herr et al. (2018a)).

The streams with the largest increases in the number of zero-flow days (Figure 12) are Back, Merrygowen and Bollol creeks, which drain the Maules Creek Mine, Boggabri Coal Expansion Project and Tarrawonga Coal Expansion Project, respectively (see Figure 3 for the locations of these creeks and developments).

Not all of these creeks actually flow for 200 days every year. This apparent anomalous increase in zero-flow days occurs because modelling indicated that the river can flow for more than 200 days per year in particularly wet years. As bioregional assessments report the maximum change in zero-flow days due to additional coal resource development, the reporting is biased towards a wet year when these maximum changes can occur.

The increase in zero-flow days in these creeks may represent a change that is greater than the interannual variability under the baseline (Figure 13), which is more likely to move the system outside the range of conditions previously encountered. Changes in many other streams are similar to, or less than, the interannual variability under the baseline.

High-flow days

Additional coal resource development is more likely to affect zero flows than high flows, reflected by the shorter length of streams likely to experience changes in high-flow days (Figure 18 and Table 11 in Herr et al. (2018a)).

It is very unlikely that more than 127 km of modelled streams will experience decreases of more than 3 high-flow days per year. There is a 5% chance that 37 km of these streams might experience a reduction of 10 or more high-flow days per year. There is a 5% chance that 31 km of these streams might experience a reduction of 50 or more high-flow days per year.

Reduction in high-flow days of at least 3 days per year is very likely in six streams:

- Back, Merrygowen, Bollol and Driggle Draggle creeks, which drain the Maules Creek Mine, Boggabri Coal Expansion Project, Tarrawonga Coal Expansion Project and Vickery Coal Project, respectively

- two unnamed creeks impacted by the Watermark Coal Project.

Among these six, Back, Merrygowen and Bollol creeks are very likely to have a reduction in high-flow days of at least 10 to 20 days per year.

The modelled decreases in the number of high-flow days are less than the interannual variability under the baseline in most locations and for most probabilities of change (Figure 17 in Herr et al. (2018a)). The streams that drain catchments near the Maules Creek Mine, Boggabri Coal Expansion Project, Tarrawonga Coal Expansion Project and Watermark Coal Project could potentially experience reductions in high-flow days comparable to, or greater than, the interannual variability under the baseline, which is more likely to move the system outside the range of conditions previously encountered.

Annual flow

Modelling predicted it is very unlikely that more than 74 km of modelled streams will experience decreases of more than 1% in annual flow. There is a 5% chance that 34 km might experience reductions of more than 5% in annual flow, and a 5% chance that 17 km may experience reductions of 20% to 50%.

Immediately downstream of mine sites, 51 km of streams are very likely to experience reductions in annual flow of more than 1%, and 19 km of streams are very likely to experience reductions of 5% to 20%. Generally, the large modelled decreases in annual flow are restricted to streams draining small catchments immediately downstream of open-cut mines. See Figure 21 and Table 12 in Herr et al. (2018a) for more information.

Reduction in mean annual flow of at least 5% is very likely in five streams:

- Back, Merrygowen and Driggle Draggle creeks, which drain the Maules Creek Mine, Boggabri Coal Expansion Project and Vickery Coal Project, respectively

- two unnamed creeks impacted by the Watermark Coal Project.

Among these five, only Back Creek, Merrygowen Creek and an unnamed creek are very likely to have a reduction in mean annual flow of 10% to 20%.

Reported decreases in annual flow are smaller than interannual variability under the baseline in all locations and for all probabilities of change (Figure 23 in Herr et al. (2018a)).

Water quality

The risk to regional stream water salinity due to additional coal resource development depends on the magnitude of the hydrological changes and the salinity of the groundwater relative to the salinity of the stream into which the water is discharged. In all the streams identified from the regional-scale modelling with potentially large changes in flow, the impact on local stream salinity depends on the relative reductions in catchment runoff and baseflow over time. Where modelling predicts a possible reduction in baseflow, this could lead to a reduction in stream salinity (Peña-Arancibia et al., 2016).

Reductions in catchment runoff are more likely to affect runoff peaks, while baseflow reductions have a more noticeable effect on low flows. In streams where modelling suggested increasing numbers of zero-flow days, it is likely that channel pools will be subject to longer periods of salt concentration by evaporation and less efficient flushing. These are conditions that favour increasing salinity of these water bodies. Creeks with increased numbers of modelled zero-flow days include:

- Back Creek (near Boggabri Coal Expansion Project)

- Merrygowen Creek and Ballol Creek (near Tarrawonga Coal Expansion Project)

- Mooki River near Watermark Coal Project.

Increases in baseflow, potentially leading to increases in alluvial aquifer and stream salinity, cannot be ruled out; however, this is not an outcome that has been reported in the literature and remains an area for further investigation. Estimating the magnitude and extent of water quality changes would require specific representation of water quality parameters in the modelling. This remains a knowledge gap.

Regulatory requirements are in place in NSW that aim to minimise potential salinity impacts due to coal resource development. See Section 3.3.4 of Herr et al. (2018a) for more detail.

Figure 12 Increase in the number of zero-flow days due to additional coal resource development

The coal resource development pathway includes baseline and additional coal resource developments (ACRD). The difference in zero-flow days between the coal resource development pathway and baseline is due to additional coal resource development. See Figure 3 for the location of the streams with the largest increases in the number of zero-flow days: Back, Merrygowen and Bollol creeks. Results are shown as percent chance (Box 5). These appear in Herr et al. (2018a) as percentiles. ‘Unquantified hydrological change – direct (mine proximity)’ indicates streams that flow through or start within a mine area. ‘Unquantified hydrological change – indirect’ indicates streams within a potential additional drawdown area.

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 1)

Streams are labelled in Figure 12. The coal resource development pathway includes baseline and additional coal resource developments (ACRD). The difference in zero-flow days between the coal resource development pathway and baseline is due to additional coal resource development. Results are shown as percent chance (Box 5). These appear in Herr et al. (2018a) as percentiles.

Data: Bioregional Assessment Programme (Dataset 1)

Explore the hydrological changes in more detail on the BA Explorer, at www.bioregionalassessments.gov.au/explorer/NAM/hydrologicalchanges Observations analysis, statistical analysis and interpolation, product 2.1-2.2 (Aryal et al., 2018b) Water balance assessment, product 2.5 (Crosbie et al., 2018) Surface water numerical modelling, product 2.6.1 (Aryal et al., 2018a) Groundwater numerical modelling, product 2.6.2 (Janardhanan et al., 2018) Impact and risk analysis, product 3-4 (Herr et al., 2018a) Surface water modelling, submethodology M06 (Viney, 2016) Groundwater modelling, submethodology M07 (Crosbie et al., 2016) Impacts and risks, submethodology M10 (Henderson et al., 2018) Surface water uncertainty analysis (Dataset 6) Summary of surface water results (Dataset 7) Surface water model (Dataset 8) Regional watertable (Dataset 1) Groundwater model uncertainty analysis (Dataset 5) Summary of groundwater drawdown by assessment unit (Dataset 1) Groundwater model results (Dataset 5) FIND MORE INFORMATION

Product Finalisation date

- Executive summary

- Explore this assessment

- About the subregion

- How could coal resource development result in hydrological changes?

- What are the potential hydrological changes?

- What are the potential impacts of additional coal resource development on ecosystems?

- What are the potential impacts of additional coal resource development on water-dependent assets?

- How to use this assessment

- Building on this assessment

- References and further reading

- Datasets

- Contributors to the Technical Programme

- Acknowledgements

- Citation